Chapter 8: Running and Resting

Dungeons should have a variety of things to encounter: friendlies, monsters, boons, banes, treasures, traps. This chapter discusses the extremes in the pacing of your dungeon: empty rooms and boss fights.

In this chapter’s (optional) activity, you will create a set piece battle, where adventurers fight a powerful monster in a room replete with tactical options.

As extreme options, these options are best used with a light touch. However, both bring an important story beat to exploration-focused, problem-solving games. Read this chapter for the theory, even if you don’t want to use a boss monster in the dungeon that you’re building for this course!

Table of contents

- Empty rooms

- Unconquerable dangers

- Dungeon lords

- Creating interesting terrains

- Optional activity: Creating a set piece fightOptional Activity

- Further reading

Empty rooms

In poetry, a caesura (Latin for “cutting”) is a metrical pause or break in a verse where one phrase ends and another phrase begins. It’s a pause in a poem that gives the reader a chance to breathe, the listener to comprehend.

Empty rooms are a caesura in the dungeon. They give a pause in the frenetic pace of exploration. They let both GMs and players breathe, reflect, and plan next steps.1

Empty rooms give your random encounter table room to stretch its legs. Although they add the needed excitement of the unexpected, random encounters can sometimes crowd a space—a puzzle room suddenly becomes a combat room, too. Empty rooms put the spotlight on the random encounter result.

Empty rooms provide a naturalistic space between factions. These no-man’s-lands are contested territory where only unaffiliated adventurers can pass, perhaps serving as envoys between these factions.

Empty rooms are also a chance to show players your dungeon lore. Because no hazards are arresting the players’ attention, details you place here will stand out. Use empty rooms to tell a story to your players about the space that they are exploring. Add art that speaks to your setting: frescoes of hunting scenes of local monsters, tapestries of recent wars, bas reliefs of the lives of saints.

Types of empty rooms

First of all, what we’re calling “empty rooms” don’t have to be literally empty. Empty rooms are just mundane rooms with minimal descriptions.

Empty rooms can be “normal rooms.” Practically speaking, most rooms in my house are “empty rooms” in dungeon terminology. A bedroom, a kitchen, a staircase, a living room. No magic fountains, no swinging blades, barely any treasure (except my rare Japanese Comus vinyl).

Use normal rooms to establish a baseline of “realism” in your fantasy adventure game. Build out some conventions that make the dungeon feel real and lived in. Don’t overwrite your descriptions of these spaces; you can use your common sense at the table to understand the contents of the rooms. A bedroom has beds, bed clothes, a rushlight lamp, a teddy bear. A kitchen has pots and pans, wooden bowls, half a jug of wine, a wooden spoon. You can come up with these lists on the spot.

Empty rooms can be hallways, foyers, and other transitional spaces. They are empty by virtue that they aren’t made to fulfill some greater purpose; they are architectural necessities.

Use transitional spaces to hint at what lies beyond. A hallway can be strewn with bones and blood as you approach the lair of a monster. A staircase has graffiti warning that you’re approaching the territory of a faction.

Treating hallways like rooms

You can key your hallways! They can be trapped. They can be bridges that are guarded by trolls. They can be checkpoints for enemy factions.

Empty rooms can, indeed, just be empty. They can be once-grand rooms now fallen into ruins and unused. They can be cellars deprived of provisions. They can be uninhabited muddy tunnels of cavern systems.

Use truly empty rooms to communicate a feeling of desolation or isolation. As players move into these spaces, use your description of the area to create a sense of time and place.

Empty, but not nothing: In case you need a little help with your empty rooms, roll 1d6 and consult the table below.

The empty room contains…

- mundane items

- an encounter table clue

- a warning

- a clue or password

- a historical mosaic, fresco, or bas relief

- truly nothing, but has an interesting shape/color/smell

I talked about building out these types of empty rooms on my blog!

Safe rooms

Related to empty rooms, a reason to breathe easy can be a room that affords the adventurers a chance to rest in the dungeon.

They can be magically protected rooms, like bonfires in Dark Souls. They can be hidden rooms, protected by their anonymity. They can be rooms with beneficial features, like altars that provide blessings or fountains that provide healing.

Safe spaces are a great reward for clever play. A trap that the adventurers effectively bypass can make a dangerous room into a safe room; perhaps the trap even continues to serve as protection against other dungeon denizens. A solved puzzler door’s optional reward is a place to rest and heal up before a large battle.

Lost Shrines & Friendly Foes: From an old-school perspective, resting in the dungeon is conventionally heretical. But convention is there to be broken. So, perhaps through an old-school lens, a “safe space” can be created but requires substantial upkeep to maintain. Two quick examples:

A lost shrine to Ishtar can be blessed by a devoted party member, causing the statue to shed occasional healing tears. However, this also attracts those who wish to see Ishtar’s light extinguished.

A giant talking spider is willing to trade a “night’s rest” in their web if provided a fresh humanoid meal. However, the spider’s payment demands double with every subsequent rest.

Unconquerable dangers

Dungeons & Dragons should have dragons in it. Not at level 16+, at level 1. To my mind, there’s no better reason to flee than a dragon. Don’t be afraid to put a dragon in your dungeon.

A sleeping dragon might be an unbeatable guardian for a beginning party and must be snuck past. A somewhat more experienced party might try and defeat the dragon to win her treasure. Either way, the dragon provides some type of challenge for the adventurers, whether they are novices or veterans.

Even for games without “dragons” in their title, the principle remains: Dungeons are most exciting when there’s not an expectation that everything within can be conquered.

Not every monster should be able to be fought. It’s good when some monsters are too powerful for the PCs at their current level. Instead of combat, the challenge becomes sneaking, trickery, or diplomacy.

Not every hazard should be able to be overcome. A door that can only be opened with a high level spell is a good reason to return once the PCs have leveled up a bit. They might return to find the dungeon has opened up in new ways since their initial exploration.

This paradigm makes sense and increases a sense of immersion in the fantastic world. Why would a dungeon be perfectly “leveled” for the players?2 When players understand that there are a mix of dangers, some defeatable through their current abilities and some avoidable only through clever play, the problem-solving nature of the game is elevated.

Dungeon lords

Dungeon lords (my poetic term for “boss monster”) are one way to introduce an unleveled encounter. Even if you intend for the dungeon lord to be defeated, they are an exercise in high-impact danger.

Dungeon lords are good hazards because they will beat the players in a fair fight. Their inclusion means that players will either need to not fight fair, or will need to solve the “puzzle” of the dungeon lord, finding some advantage that lets them overcome their resistances, their high-impact attacks, or their numerical advantages.

The PC party as a singular monster: It’s true this is not a monster design course, but one important point about singular “boss” monsters is they can easily lose out in “action economy” or actions over time versus the party. This can make encounters very anticlimactic. The reason is because the average fantasy adventure party consists of 4 to 6 PCs (plus as many hirelings) and therefore your players are often taking multiple actions on their turn in a coordinated fashion. So, when thought of as a monster, a player party of even level 1 PCs is a 4-6 hit-die creature that can make 4-6 attacks per their turn and 1-2 of those attacks are magical or increase damage potential (e.g., backstab). By contrast, an ogre is a 4 hit-die creature that has only 1 attack. Therefore, it’s important to supply your boss monsters with extra actions per round or have them supported by an honor guard of “elites” or “pawns” to help provide extra enemy actions.

You don’t have to have a “boss.” OSR dungeons aren’t intended to feel like video game dungeons, where you clear every room, beat every monster, and defeat the boss to get his power-up. That said, lots of good modules have them. Dungeon lords are a classic for a reason!

Puzzle combats

One way to structure combat with a dungeon lord is to infuse puzzle elements into the lord’s lair. In addition to attacking the dungeon lord, adventurers will need to interact with the puzzle in order to be successful. The pacing of combat, with the slow reduction of PC resources like hit points, puts a timer on the puzzle.

For example:

- The mummy is immune to magic until the five sacred flames are kindled around its tomb.

- Whenever a colored dragon statue is exposed to a certain element, it explodes. Position the red dragon statue near the boss and cast fireball on it to deal massive damage.

- The City Golem is huge. The combat takes place on its gigantic body. Players crawl over it to stab its vulnerable runes on its back, its head, and the back of its left hand.

Puzzle elements can rely on interesting terrain. This can be as simple as pillars that block a dragon’s breath attack, allowing smart players to position their characters behind them whenever the dragon breathes in. It can be more complicated, too, with interactive elements being key to negotiating the fight: levers to pull, runes to stand on, machines to pilot.

Researching to defeat the beast

A good reason to return is to try and solve the puzzle of the dungeon lord fight. Sometimes you bump into Dracula and need to retreat and consult your local sage, Van Helsing, before you continue with your crawl.

Puzzle elements can persist throughout the entire dungeon, not just a single combat. For example, a vampire dungeon lord might plague the PCs using hit and run tactics throughout the entire dungeon, becoming a mist whenever the players get the upper hand. Only after the adventurers have reactivated the sun machine, bringing light to the dungeon that robs the vampire of his mist form, can the vampire be faced in a “fair” fight.

“Towards a Taxonomy of ‘Trick’ Monsters”, Gus L.

“Special abilities are important, and really a very necessary part of good monster design. They become more important the higher level the party is, both because the players will be well acquainted with regular combat, and because at higher levels combat encounters often take a lot longer. Special abilities, either by making a monster susceptible to certain tactics or by making the monster more dangerous make combat quicker and more dangerous. Even at first level monster special abilities are interesting and build setting.”3

Phased combats

One way to make boss fights feel different is to use different stat blocks, techniques, or enemy compositions during different phases of combat.

One way to make boss fights feel different is to use different stat blocks, techniques, or enemy compositions during different phases of combat.

D&D 4E had the concept of being “bloodied” when a character was at 50% of their total hit points. Use this paradigm to have a two-stage fight. When your dungeon lord loses 50 hp of their 100 hp total, they gain a second action, become immune to first level spells, and summon 12 minions to join the fight. You can build this out as well, having three or more phases to your combat.

As part of this technique, you can use different monster stats sequentially during the encounter. Once the werewolf is bloodied, he transforms into his “final form”—a twenty-foot tall lupine monstrosity, an undulating mass of fangs and hair and golden eyes. Once the cultist leader is killed, his sacrifice summons Bae’lobhath the Devourer. The two monsters you use might be mechanically very different even if they’re thematically unified.

Balance is an illusion

Don’t fall into the trap of planning a perfectly calibrated fight where the dungeon lord is defeated and every player has 1 HP remaining. Your players will surprise you and clever play should be rewarded. Rolling a boulder onto the dragon’s head and taking it out in the surprise round is valid and more exciting to the players than a three-hour combat session with phased encounters and exploding terrain.

Weird attacks

Attack every part of the character sheet. Dungeon lords are great tools to employ this maxim. Because they have so much narrative power, you can use them to inflict all sorts of weird effects.

Attacks don’t just have to tick HP down. They can destroy weapons or armor. They can drain XP. But they can do even weirder stuff, too! They can make adventurers forget their own name. They can fill item slots with emotional baggage. They can change an adventurer’s kith or kin.

Telegraphing attacks

Dangers should be telegraphed. Weird attacks are no exception. The weirder and more deadly a dungeon lord’s power is, the more need there is to telegraph the attack. Dungeon lords can “wind up” an attack at the end of a round. Smart players can then take actions to mitigate the attack before it’s released: hiding behind objects, casting defensive spells, taking evasive maneuvers, etc.

Puzzling, changing, bizarre, but not out of the blue!: I think it is important to ensure that all of the different types of combat are thematic to the dungeon lord in such a way that it could be reasonably guessed by the players. This ensures that players are not totally caught off guard by an effect. This helps maintain the (magical) realism of the game. To try to ensure this in my own games/dungeons, I try to take in account an adversary’s aesthetics, room context, and history.

For example, an ogre cook might release blackbirds from a pie (phase combat), create pepper clouds (weird attack), be aided by bugbear sous-chefs (phase combat), create a rain of knives (weird attack), make the floor lava by kicking over a boiling cauldron (phase combat), or break-down only if their souffle is deflated (puzzle combat).

Creating interesting terrains

When possible, combats should take place somewhere cool.

Cool encounter spaces provide potential energy—they give the players (and the GM!) stuff to interact with. Build monster lairs and dungeon lord rooms with a few pieces of interactable scenery, including dynamic terrain, sensory information, and usable objects.

Terrain

Create spaces that tell a story. Combats often inhabit a liminal space, set between safety and danger, stable and unstable, solid and liquid, cool and hot, heights and depths. Exploit these contrasts.

For example:

- A bridge over a chasm

- Hanging chandeliers

- An oil slick

Sensory information

An adventurer’s understanding of their environment is based on the limits of their senses. By default, the dungeon is a dark and difficult place. Place further restrictions on the party’s vision, hearing, and other senses to provide additional challenges.

For example:

- Smoke near the room’s ceiling, choking or blinding tall characters

- The area is half-filled with murky water

- Illusory objects and creatures

Objects

Empty rooms are boring. Each space should be scattered with interesting items. Set pieces can be picked up, hidden behind, or smashed through.

For example:

- Hanging tapestries

- Braziers of coals

- Silk dressing screens

Before/after states

As part of a phased combat, you can change the terrain of a monster lair mid-combat. This forces the players to adopt new strategies mid-combat and keeps the pacing from becoming stale. For example, when the dragon enters stage 2 of the fight, the results of its thunderous movements take a toll on the dungeon. Parts of the floor collapse, with pits opening throughout the room, and half of the columns that once protected the party from the dragon’s fiery breath collapse. The combat is suddenly much more dangerous!

Before/after states can extend to the entire dungeon as well. Once you trap Satan in the block of ice, the rest of the hell dungeon freezes over. Leaving the dungeon, the adventurers will find new paths to explore. Lava flows are now traversable solid rock. Boiling lakes are now swimmable.

Optional activity: Creating a set piece fightOptional Activity

If you want to include a big boss battle in your dungeon, use this optional activity to think through your set piece fight.

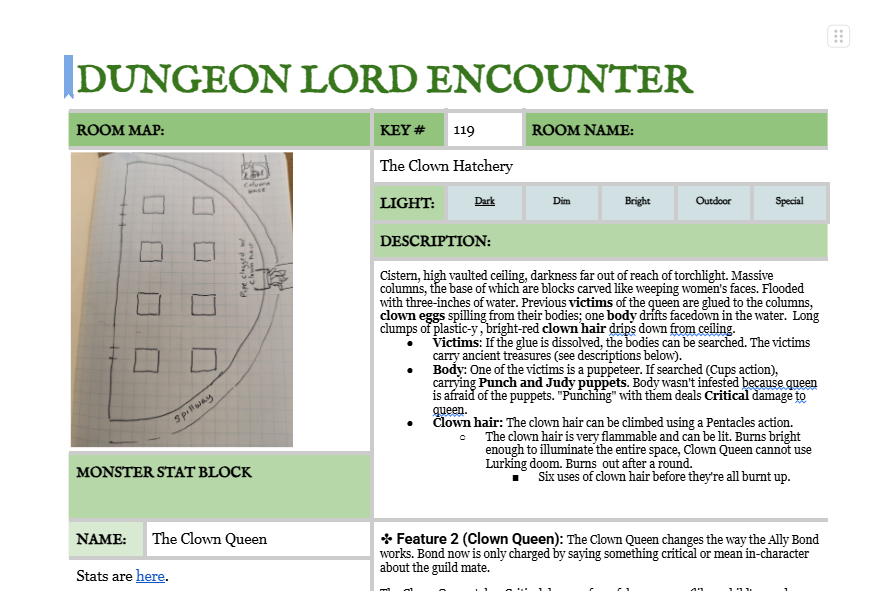

For this activity, open the workbook that you created in chapter 2. Navigate to page 9: Dungeon Lord Encounter. For each step, write your answers down here.

Step 1: Name your room

First, establish the location of the dungeon lord’s lair on your map.

- In your Designing Dungeons Workbook, flip up to your map on page 4. Select one of the rooms to house your dungeon lord.

- On page 9, write the room number in the “Key #” space.

- Give the room a memorable and evocative name. Write it in the “Room Name” white space.

Step 2: Define your dungeon lord

Who is the lord of the dungeon? Use your system’s monster manual to select a cool creature for your players to fight.

- Give your dungeon lord an evocative name.

- Copy and paste the dungeon lord’s stat block into the white space under the name. *

- Write one or two sentences describing the dungeon lord’s behavior, their personality, and roleplaying notes for how to portray them at the table.

- Simply define what the dungeon lord likes; things it wants to accomplish or wants to obtain.

- Simply define what the dungeon lord dislikes; types of adventurers it will prioritize in combat, special things it will avoid, situations it won’t place itself into.

* This is system dependent. His Majesty the Worm is not a particularly crunchy game per se, but a dungeon lord’s stats can’t fit into the space that I set here. Alas! A monster for a game like OSE should fit there fine, though!

Step 3: Write the room description

Create an interesting space for a cool combat to take place. Write a basic description of the room in the “Description” space: what kind of room it is and what the characters can immediately notice.

- Can the dungeon lord see in the dark or do they keep their lair lit? Underline one of the “Light” levels (Dark, Dim, Bright, Outdoor, or Special).

- What is the terrain? Define what the space looks like and if there are any special rules for movement, climbing, hiding, and so on.

Step 4: Create a special monster feature

Consider whether you want the puzzle of the dungeon lord to be solvable through a direct fight or if there should be an activity that needs to be completed to defeat the monster. Write towards considerations of the strength of your party and the strength of the dungeon lord: its special abilities, its resistances, its vulnerabilities. Determine if you want the dungeon lord to have different combat phases.

Answer the following questions in “Feature 2 (MONSTER)”:

- Does the dungeon lord have a phased combat?

- When are the different phases triggered?

- What different stats are used for the dungeon lord (et al) during the different phases?

- Is there a puzzle the players need to solve to interact with the combat? What is it?

- Does the dungeon lord have a special attack?

- If so, how do they telegraph the attack?

- Does the dungeon lord have any special resistances?

- If so, what is a hint about the resistance?

- Does the dungeon lord have a special vulnerability?

- If so, what is a hint about the vulnerability?

- Are there any special rules for the players due to the proximity of the dungeon lord?

If the answer to any of the questions are “no,” just skip them.

Step 5: Create interesting room features

Next, select special pieces of terrain, objects, and environmental effects that will help create a charged encounter. Determine if you want the terrain to have a before/after state. Answer the following questions in “Feature 3 (SET PIECE ENCOUNTER)”:

- What interactable objects are in the room? Define a few things the players can pick up, wield, hide behind, smash, activate, move, etc.

- Are there any special rules for the players due to the environment?

Step 6: Draw the room map

Draw a simple map of the room.

If your game uses grids to track movement during combat, take this time to create the map that you’ll use when running this encounter.

Step 7: Determine treasure

Decide the treasure your players will get if they defeat the dungeon lord. We’ll talk more about treasure in the next chapter, but sketch out some simple rewards in this step.

Answer the following questions:

- Does the dungeon lord have enchanted items that the players can loot? What are they?

- Does the dungeon lord’s lair have treasure that can be sold in civilization like art, relics, heirlooms, finery, books, jewelry, etc.? What is it? How much is it worth?

- Does the dungeon lord’s lair have a cache of coins, gems, or other currency? How much is there?

Having completed all the steps, you should now have a clear picture of what a dungeon lord battle might look like. As always, you can come back later and refine the things you wrote today, if you want!

To see the sort of boss fight I put together, check out at my completed Dungeon Lord Encounter.

My dungeon lord is the Headless Mage! In fact, my dungeon will be named after this villain. Read about the dwelling-place of the Headless Mage here.

Further reading

What good are empty rooms?

In the episode “A Malignant Presence” of the excellent Into the Megadungeon podcast, Luke Gearing talks about how his players essentially use empty rooms as a tactical currency. Check it out (and the rest of the podcast) for insights into how these spaces work as important contributions to the total experience.

How can I simulate video game boss battles?

I played World of Warcraft for a while. A huge chunk of the game revolves around big, scripted boss fights with interesting mechanics. Nearly all of these boss fights would be pretty shitty if you ported them to a tabletop RPG…However, there are a ton of boss mechanics in the game, and once you cull all the inappropriate ones (safety dance, reflex-based stuff), there are still some that can be useful. I’ve tried to articulate them below in a system-neutral way.

Arnold K. of Goblinpunch deconstructed the Boss Mechanics of World of Warcraft, laying out different schemas you can use to create interesting, puzzle-esque combat encounters.

Additionally, in Action-Oriented Monsters, Matt Colville outlines a technique where monsters trigger specific actions on specific turns of the battle. The end goal is to create fights that feel more dynamic, where the monster changes tactics and reveals new abilities as the fight progresses. The technique also helps address the common problem where boss monsters can get overwhelmed by the players’ number of actions.

What’s a good technique for representing monsters with lots of “moving parts”?

Build complex monsters by splitting their HD and nesting it as components. The more complex your nesting the harder the monster is to defeat. Going five layers deep implies a powerful “boss” monster that will prove a challenge.

Imagine having to cut down a kraken’s many tentacles before you can get close enough to its beaked head to actually kill it! Sounds like a cool battle, right? Mindstorm’s Nested Monster Hit Dice is a method to create “puzzle monsters” by representing a single monster’s many parts and powers as separate characters, each with their own pool of hit points.

How do I create actionable, solvable “puzzle monsters”?

I think a key part of elevating a puzzle monster into something that can take up an entire adventure scenario is context. The monster is just one piece of a greater situation which must be reckoned with. The situation still contains puzzle elements, a fantasy nature, and connections to the monster that intrinsically tie them together. But the point is that there’s more to consider than just the physical creature itself.

Dwiz at KnightattheOpera lays out a clear procedure to create a solvable puzzle monster encounter: come up with a monster idea, decide on their goal, figure out what the solution to the fight is, then work backwards. Read the full article, replete with extended examples, here.

All spot art in this chapter (and this course!) by BertDrawsStuff. ↩