Chapter 7: Talking and Fighting

This chapter builds on your previous work to define key characters and creatures for your players to encounter: intelligent NPCs, rival adventurers, common critters, and mythological monsters.

We’ll start with a discussion on monsters (your reason for fighting). As an activity, you’ll riff on those concepts to get your brain going. Then, we’ll discuss intelligent characters and factions (your reason for talking) and work on an activity to crystalize the NPCs you place in your dungeon.

Table of contents

- Monsters

- Activity: Ideating monstersActivity

- On the non-player character

- Who do you meet in the dungeon?

- What the hell are those people doing?

- Activity: Build out dungeon denizensActivity

- Further reading

Monsters

In chapter 3, you began to think through the sort of denizens that might dwell in your dungeon. Refresh your memory by looking at your Dungeon Worksheet on page 3 of your workbook before you read this section.1

Reusing monster stats

This course is about dungeon design, not homebrewing critters in your system. For our purposes, I recommend using creatures that you have readily at hand in your system’s monster manual.

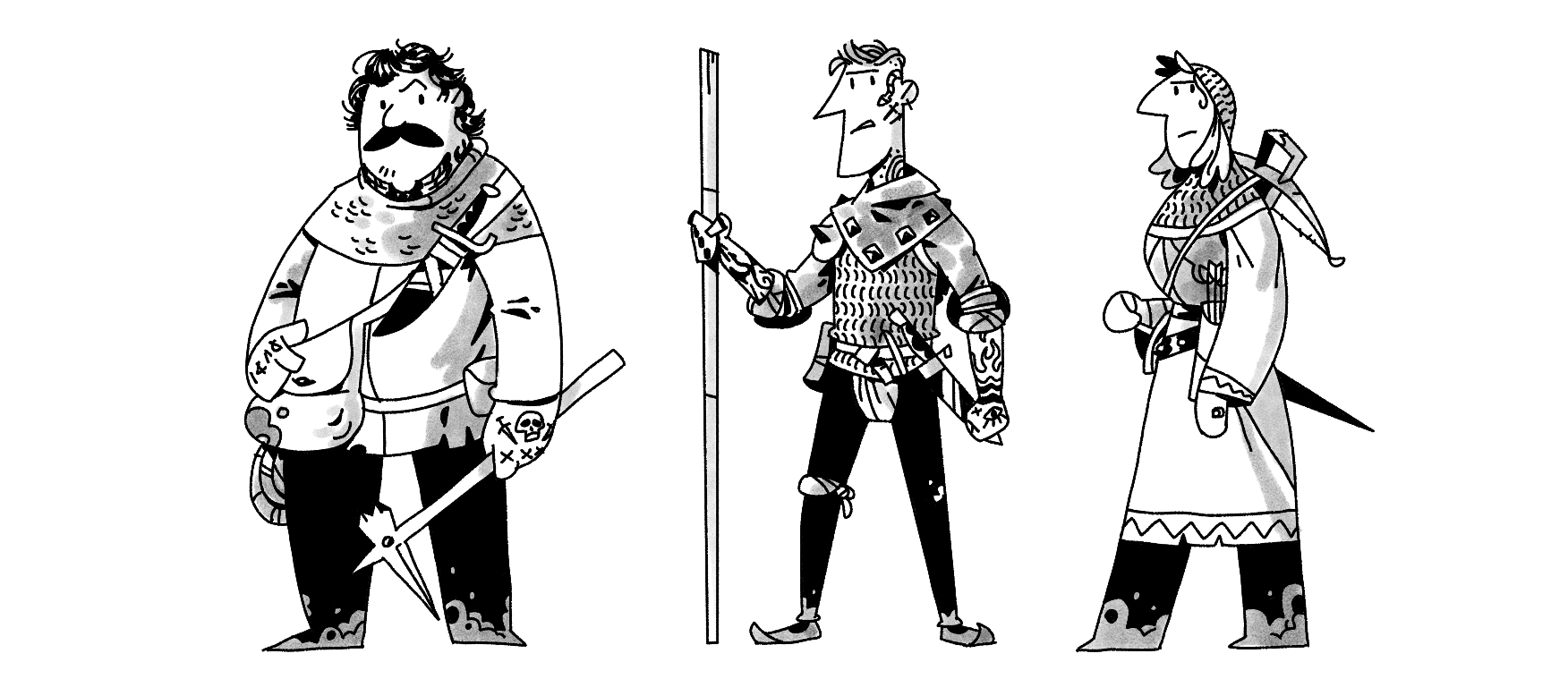

Dungeon denizens

Throughout this chapter, we use a small variety of common words: creatures, characters, NPCs, and more. Broadly, this refers to the class of “humans, demi-humans, thinking characters, monsters, animals, etc.” of beings that can be in a dungeon. We broadly refer to the group inclusively as “dungeon denizens.”

If you find yourself wanting to use a monster for which you do not have stats, a simple solution is to “reskin” existing monsters—meaning keeping the same stats but describing the monster in a different way, with different names and different mannerisms.

To create an interesting creature that fits with your dungeon’s theme and background, start with a classic mythological monster. Then, exaggerate one aspect. People can only handle one new idea at a time, and changing too many things makes the creature lose its coherency. The exaggerated aspect will make the creature feel fresh and reinvigorate the player’s interest even in the most classic and overused monsters.

For example:

- A zombie, but it’s animated by a swarm of locusts

- A giant spider, but its legs are human fingers

- A skeleton, but it’s covered in blood and in love with the skeleton inside of you

Math-free way to reskin a cat: For instance, monsters such as goblin, orc, spider, gelatinous cube, skeleton, bats, wight are quite typical and perhaps a little boring, so I tried to think of interesting alternatives that still might use the same stats.

This yielded: goblins as “half-manculi” (‘cause 1/2 HD), orcs are “whole-manucli” (‘cause 1 HD), and spiders are now “trapped-door spiders” (because it’s interesting to have a fantasy predator that uses dungeon doors). Finishing the list, the gelatinous cube becomes a “jelly wizard” (because it has many HD and can paralyze) and bats become “spell-ravens” or “spavens” (because what happens when a talking-bird hangs out with a wizard). And let’s make the undead suggestions have a little more oomph with typical skeletons becoming “disturbed dead” (why are they bothered?) and the wight, another “big” antagonist is now a “corrupted paladin” (has to be history there).

Calibrating threat

You might be asking yourself at this point: How many monsters does my dungeon need? How deadly should they be?

Good questions! As with many things, the answer is “it depends.”

The old-school mindset is to eschew balance. A dungeon peopled entirely by man-eating giants would be a disastrous module to run for level 1 characters if the expectation was the players would need to fight each and every one of them. But in an old-school milieu, players can also hide from the giants, poison their soup pots, or hire a rival tribe of giants to fight for them.

Alternatively, a game like D&D5E or Pathfinder has challenge ratings and expectations of X monsters versus 5 PCs of a certain level. The answer to “How many monsters?” will be different based on the system you’re prepping for.

Do the needed calibrations of your system as part of your work in this chapter to make sure you’re achieving the goals of your game.

I think about it like a chess game: even, tough, and fair. Create a mix of pawns, elites (bishops, rooks, knights), and royals.

- Pawns: A common but weak type of monster; there should be many pawns

- Elites: Stronger monsters with a gimmick; there should be a few elites

- Royals: Boss monsters that are very powerful; there should be only one or two royals

Fighters as a unit of calibration: In many old-school fantasy adventure systems, PC level is equal to monster Hit Die (HD). For example a 3rd level fighter is equivalent to three 1 HD orcs, but a single 4 HD ogre has a slight advantage. So, a quick way to eyeball suitability of a monster is to see how it compares to a starting PC fighter (or knight, barbarian, wastelander, whatever it is in your system).

Pawns

Pawns are low level enemies that can be found throughout the dungeon. On their own, pawns don’t present much of a combat challenge, but are dangerous in high numbers.

Because of their ubiquity, pawns should make sense in the context of your dungeon theme and background. Nobody should say “Why is this in this room?” Vermin like rats or slimes are a great kind of pawn because they make sense in many contexts. Similarly, patrols of guards of the local faction always make a great default pawn.

Basic does not mean boring: As in chess, the “pawns” in your dungeon are not just throw-away pieces; many a chess game has been won through excellent pawn use. Let’s replicate that in our dungeons as well.

Elites

Think of the power pieces like bishops, knights, and rooks. You can almost characterize them as different types of monsters:

- Knights: Monsters defined by their high maneuverability, forcing the PCs to engage them in different ways. Flying monsters like bats and harpies won’t fight 1x1, but dive bomb the adventurers or lift them into the air and drop them off of cliffs. Climbing monsters like spiders or lizardmen can perform hit and run tactics, attacking at range and then running into spaces the PCs can’t follow.

- Rooks: Monsters defined by their strength and invulnerability. Because of the difficulty of taking them on in combat, I think of rook monsters as having tropey limiters. The monster might be strong but stupid, like a golem. Or they might be invulnerable but slow, like a bloodybones.

- Bishops: Monsters defined by their intelligence and mystic power. These monsters can be glass cannons—able to deal high damage at a distance, but physically weak, like rival sorcerers. They can also attack characters in unusual ways, draining attribute points, XP, resolve, etc., like specters.

“The Only Two Enemies You’ll Ever Need,” Dwiz at KnightattheOpera

I have two types of enemies that I fall back on if I don’t have something interesting or appropriate prepared:

A. Powerful but dumb

B. Weak but cunning 2

Royals

These are monsters that define the space like a king or queen in chess. When the king is defeated, the game is over. Similarly, the king can represent the head of a local faction: if the great goblin is defeated, the goblin horde scatters.

The queen is the most powerful piece in chess, and represents a particularly deadly foe: the dungeon lord. (We’ll discuss dungeon lords in the next chapter!)

In your dungeon, the queen and king can be the same foe, e.g., the great goblin is the most deadly monster in the dungeon. But, like in chess, it does not have to be the case. For example, a dragon (queen) might have kidnapped the princess (king). If the players rescue the princess through stealth or trickery, they don’t have to defeat the dungeon lord dragon. The princess NPC is the linchpin that changes the state of the game, moving from exploration to escape.

Monster lair or wandering monster?

When you have a pool of monsters to place in your dungeon, an essential question is whether you place them into rooms or if you put them on the random encounter table.

Monsters placed into a lair create an obstacle for crossing that room. They define that space. Wandering monsters on the random encounter table add a dynamic danger to exploration.

You want to avoid the feeling that monsters wait in empty rooms just to attack adventurers. Even a small level of consideration towards the practical realities of the monsters’ daily routine gives a sense of verisimilitude. Mixing static and dynamic elements helps the dungeon feel more “alive” and makes it a more interesting place to explore.

For example, in an ogre’s castle you might have:

- Mother Maggot, the mama ogre, spends most of her days in her foul kitchens. This is her “lair,” and she’ll be encountered here unless there’s a reason for her to have left (e.g., heard a loud noise).

- Mother Maggot’s three bully boys, Wart, Pimple, and Zit, roam the castle avoiding various chores. They can be found complaining about chopping wood, playing dice instead of emptying the chamber pots, and arguing with each other instead of feeding the captives. They are encountered via the random encounter table, and the room they appear in changes the description about what they’re currently doing.

A trick from Castle Blackmoor: Supposedly, Dave Arneson, D&D’s co-creator, used to just draw wandering monsters from nearby rooms instead of having a separate table when a random encounter was rolled. This might be a good tactic for your game as well.

Activity: Ideating monstersActivity

In this activity, you’re going to put the theory you’ve read so far in this chapter to the test and think up some bespoke monsters for your system.

Spend time on the stats of your system here to experiment with different configurations. Focus on monsters you want to use for your dungeon—the ones you wrote down on your Dungeon Worksheet on page 3 of your workbook. But, if you feel so inspired, riff on monsters you won’t use as well. The specifics are less important than the experimentation.

Stats as bear

When writing stats, you don’t have to be overly elaborate. Saying “Stats as bear” or “Stats as dragon but with breath weapon of enfeebling ray” is perfectly fine for our purposes.

For this activity, open the workbook that you created in chapter 2.

Navigate to page 7: Here Be Monsters. For each step, write your answers down here.

Make sure you have the RPG that you’re designing for nearby. You’ll reference it during this exercise as you plan out the different monsters.

If you want to see my version of the workbook with this activity complete, check it out here.

My version of the workbook is here!

Step 1: Mix two monsters together

To get started on ideating on different kinds of monsters, combine the stats of two monsters together.

- Select two monsters from your system of choice.

- Consider how they can be merged together thematically, and what implications that would have on their stats.

- Write a stat block that takes something from one monster combined with elements of the other monster.

Example: Zombie bear

Stats as bear, but with the standard undead vulnerabilities and resistances.

Step 2: Put a twist on a classic monster

Take a boring monster and make them interesting by introducing a weird new detail.

- Select a normal monster for your setting.

- Write a one or two sentence description that makes the monster seem refreshing and weird.

- If this would affect the way they fight, change their stats in a minor way. Write a sentence explaining how they are changed.

Example: Peacock cockatrice

Stats as cockatrice, but petrified victims are turned to gold instead of stone.

Step 3: Reskin a monster

Use the stats of one monster to describe a new monster.

- Choose one of the monsters you want in your dungeon that doesn’t have an entry in your monster manual.

- Choose a monster close in “power level” whose stats you can borrow to represent the new monster.

- Write a sentence or two for your notes to explain how you’ll use the monster at the table.

- Write a sentence explaining what the new monster looks like.

- Write a sentence explaining what its combat stats will be.

Example: Subterranean white ape men

Stats as orcs, leader of group will carry a laser gun (stats as wand of lightning bolt)

Step 4: Strong but dumb monster

Select a monster from your monster manual that is dangerous to fight head on but is able to be out maneuvered by clever players.

- Choose a monster for your dungeon that is physically powerful but easily tricked.

- Write a sentence or two for your notes to explain how you’ll use the monster at the table.

Example: Two-headed troll, always arguing with itself

Step 5: Weak but genius monster

Select an intelligent monster from your monster manual that can scheme against the PCs but is not strong in a direct fight.

- Choose a monster for your dungeon that is mystical or hyper-intelligence but is physically weak.

- Write a sentence or two for your notes to explain how you’ll use the monster at the table.

Example: Brain in a jar, controls the dungeon’s traps

Step 6: Monster with resources you can harvest

Look through your monster manual and select a monster that yields an interesting resource when defeated.

- Choose a monster that has a resource that can be harvested from its corpse or produces something usable while alive.

- Write a sentence or two for your notes to explain how you’ll use the monster at the table.

- Write a sentence or two imagining how the players can make good use of this resource in your dungeon.

Example: Biscuit golem

The biscuit golem is an animate gingerbread man. Eating them is like drinking a potion, with effects based on their ingredients. Shortbread biscuit golems shrink the eater down to 1’ tall for an hour, for instance. This would allow players to traverse a tiny door.

Step 7: Share with friends

Writing six monsters is hard work! The last step is to go show your friends. Share the work you did with your RPG community (not your players!). Post it on your blog, on your social media, on Reddit, in your Discord channel, wherever you hang out with other nerds. Invite feedback to see what experts in your system think about your monster kit-bashing.

The Punnett-Square method: Because of their frequency, pawn-type monsters offer a way to characterize the theme of the dungeon. Simply doing “3 HP, 1d6 dmg, armor leather” is going to get boring for the party because encounters will become a grind of sameyness.

I use a Punnett-Square method 3 to add character to these pawns and spice up the encounter. I don’t use complicated math; I just add variation. Let’s look at my “half-manculi” monsters, which are restated goblins in the design of vat-grown wizard mistakes with one big exaggerated feature.

- Minimal HP range x special attack: Big Ears 2 HP, 1d4 dmg spear, flap ears to fly & hear very well

- Low HP range x mundane dmg: Sniffer 3 HP, 1d4 dmg snot rocket as sling, snot lowers AC -1

- Mid HP melee x mundane dmg: The Maw 5 HP, 1d6 bite damage

- Highest HP melee x special attack: “Whole-manculi” - just two half-manculi stacked on top of each other; has the abilities of both half-manculi

Now you can see that two separate encounters with 4+ of these creatures might have vastly different outcomes. This can keep things fresh and even low-level monsters feeling dangerous.

On the non-player character

In chapter 5, you began to define characters using their goals and the methodologies. We continue this work here.

Two sentence NPCs

As we discussed in chapter 5, you can define an NPC using just two sentences:

- What does the character want?

- What can the character give the PCs?

These questions are the most important because they’re the most salient for players. They give the players something gameable to interact with.

And to reiterate: it’s okay if the players are not interested in what the NPC wants or offers. An NPC who wants to extinguish all life on Earth (because only then can it be reborn perfectly) and offers a painless death is still an interesting NPC to interact with. Their desires put them at odds with the players. The two sentences still provide a gameable experience.

Four sentence NPCs

Maybe two sentences aren’t not enough for your preference as a GM. You want to provide more robust and more realistic dramatis personae for your players to interact with. Fair enough! Here are two more sentences:

- What does the character like?

- What does the character hate?

Insightful role-playing that appeals to these likes should provide opportunities to avoid hostility or gain leverage. Conversely, roleplaying that touches on what the character dislikes is like walking into a booby trap. The NPC’s reaction worsens; they might try to shut the conversation down or even react hostilely.

And, just like good traps, an NPC’s “likes” and “hates” should be broadcast with clues. A smart player shouldn’t try to bribe the straight-laced guard captain with the trimmed mustache who does everything by the book.

Five sentence NPCs

If that’s still not enough for you, here is a fifth: leverage. Leverage is a secret, hidden alliance, or a weakness that allows players to have an outsized influence on the NPC or faction; a sorta cheat code. Finding leverage can be the reward for a sidequest or smart play.

Who do you meet in the dungeon?

One way to categorize your different NPCs is to think of them as:

- Dungeon people: Normal folks doing weird stuff in the dungeon

- Social puzzles: NPCs that offer roleplaying/problem solving opportunities

- Weird little freaks: Funny little guys to talk to

Dungeon people

Dungeon people are “normal” folks who happen to be in the mythic underworld. Dungeon people are usually humans or demi-humans, but not always. An elven big game hunter who descends into the underworld in search of monstrous prey is a “person,” even though they’re acting strange. A dire spider with a job, a wife, 1,000 babies at home that are hungry, and worried about drowish taxes is also a “person” even though they’re not humanoid. Basically, dungeon people are NPCs whose baseline motivations are understandable to the players.

Dungeon people might include:

- Characters of the “adventuring class”

- The Two-Bit Chicks are a rival band of adventures. They might swap rumors, join the PCs to fight a challenging monster, or rob the PCs if they’re looking weak.

- Dungeon merchants

- Grinnin’ Grimnir the goblin hauls a huge pack and sells gear to adventurers such as torches, potions, and partially completed maps

- Nick Nack the gnome purchases dungeon goods from the PCs, including monster rations, alchemical reagents, and ancient relics.

- City NPCs that are lost or out of their depth

- Thonas of the Antiquities Guild is in the dungeon to take rubbings of ancient runes that are found here; the mercenaries he’s hired will abandon him if the going gets rough.

- Dungeon locals that are more or less “normal”

- Gurgle the gargoyle is pretty bored and willing to swap stories with whoever happens by. His sense of humor is awful, though.

- Ulvira the witch left the troubles of the “real world” behind long ago and now lives in the dungeon full time. She’ll trade for things from the surface she can’t make herself. Be careful, she has a fierce temper and “turn you into a newt” isn’t an idle threat.

OD&D lists many types of humanoids for the players to encounter: swashbucklers (who are different from pirates, apparently), bandits, vikings, amazons, etc. These are all examples of dungeon people.

You can add a twist to these NPCs by ratcheting up their “obsessions.” For example: (humanoid) Magicians 3+1 HD, AC 10, dagger, spells 4/2/2 can become:

THE DREAMING MAGE: A singular figure draped in voluminous red and gold robes the color of a setting sun. Eyes are always closed, yet reacts as if they see all. Those who have survived encounters with this semi-transparent apparition claim attempting conversation seems to lead to disastrous ends. Yet, those same survivors report friends being lured away by the mage’s needs never returning. Spells: (1) Charm Person, Magic Missile, Light, Hold Portal (2) Mirror Image, Wizard Lock, (3) Lightning Bolt, Monster Summoning I

Social puzzles

Some NPCs are difficult to talk to because their motivations are strange or because they have an outsized power differential with the PCs. With these social puzzles, the stakes can be higher than with regular dungeon people. Players need to think about the goals, likes, hates, and leverage of the NPC in order to solve the puzzle and roleplay a successful interaction.

For example, Bilbo’s riddling conversation with Smaug the Dragon was a social puzzle. How do you talk to a creature that can swallow you in a single gulp? How do you get information from them (flatter them so that they show you their armor, allowing you to spot the weak points) without triggering their wrath (at which point they fly to Laketown and burn it down)?

Social puzzles can include:

- Characters with more physical or magical power

- The Lady of the Well is considered ancient, even among the elves. She carefully tests the hearts of those who enter her domain. She punishes the wicked, but has been known to give magical gifts to those with pure intentions.

- Characters with a higher social rank 4

- King Gulfame wants to know why you were defiling the bones of his ancestors in the pyramids and what the day star that’s appeared in the sky foretells. Answer wisely, or “dungeon” will become very literal.

- Characters that fundamentally see the world in a different way than the players

- Ramizer is a flesh-entrapped star. He’s spent aeons watching life evolve on Earth. He’s puzzled by individuals of a species, not understanding that they don’t understand their own development from single-celled organisms. His questions are bizarre, but his perspective on the dungeon has invaluable clues due to his perception of long time.

Making languages matter

When creating NPCs, don’t neglect to address the myriad languages spoken by the adventuring party. Having different creatures speak different languages—or providing contextually different information based on the language spoken to them—can reward adventurers’ linguistic ranges and give different players a time to shine.

Weird little freaks

Some NPCs aren’t fully developed people but are instead kind of gimmick characters. These weird little freaks give humor and texture to your world, and sometimes are more memorable than the most dramatic fantasy adventures.

Weak little freaks can include a goblin named “Glorp, King Under the Bucket” or a rhyming talking door. Most dungeons benefit from the inclusion of one weird little freak to talk to.

What the hell are those people doing?

Define both your NPCs and monsters with a simple personality trait or a task that represents their “default state.” A strong personality trait can help guide your roleplaying with that character and help you make decisions about what they would or wouldn’t do.

You can also think of a personality trait as “what this character is doing here.” Dungeon denizens live outside of civilized society and tend to be obsessive and single-minded in the pursuit of their goals. (Their habits may be esoteric, immoral, impolite, or grotesque…which is why they’re in the dungeon doing it.)

Using old-school reaction rolls is another axis to use to define these NPCs. On a “hostile” roll, the character/creature will dislike or work against the PCs in a way defined by their personality. For example, a hostile merchant NPC will raise their prices or try to swindle the players. Similarly, on a “friendly” roll, the NPC follows its core personality trait for the PCs’ benefit; an aggressive character might see the PCs as kindred warrior spirits. On a “neutral” roll, the character or creature pursues their personality trait or task to the best of their ability, neither helping or harming the players by default.

Just seconding that, from an old-school perspective, the encounter reaction roll is a very powerful tool because it creates more space for diplomacy. I’ve never liked “hostile, may attack” so instead I add “extort”; it feels like hostility, but with a clear signpost to violence. On the other end of the perspective, I like “mistaken identity,”, meaning that the monsters/NPCs believe the player party to be someone they are not, more than “indifferent, may negotiate.”

This personality list is not exhaustive, but covers a lot of common ground.

Aggressive: The NPC or creature is spoiling for a fight, and will try to engage in combat even when the odds are stacked against it.

Benevolent: The NPC will try to help the adventurers by default, providing healing, food, shelter, or other necessities.

Coward: The NPC or creature will avoid fights if at all possible.

Curious: The NPC or creature is interested in learning more about the adventurers, the dungeon, or a specific secret that’s near at hand. They’ll risk their safety in pursuit of learning more about their goal.

Guardian: The NPC or creature is trying to protect a place, a secret, or another character. They’ll try to drive the adventurers off but engage in combat if necessary.

Lord: The NPC perceives themselves to be in charge and acts accordingly.

Mercantile: The NPC is here for profit. They’ll attempt to engage in commerce or take steps to secure a long-term enterprise.

Mindless: Covers the range of unthinking, autonomous NPCs.

Predator: Looking for food, will fight to get it, but not if the going gets tough.

Prey: Looking to avoid becoming food, will run if they think you’re a threat, will stand and fight if cornered.

Questor: The NPC is looking or hunting for something, and will only fight in pursuit of this goal.

Servant: The NPC or creature acts in service of another. Will do what commanded against their better judgement unless the going gets really tough.

Variety is the spice of life

It’s nice to have a variety of NPCs: some helpful, some shifty, some weird. Some NPCs should be regular people in a bad situation. Some NPCs should be barely human.

It’s nice to have a variety of monsters: some tough, some easy, some that attack on sight, some that might leave you alone unless they’re hungry, and some that are friendly.

Not every option needs to be used in this one dungeon, but across your campaign it’s nice to employ a variety of different dungeon denizens.

Activity: Build out dungeon denizensActivity

In this activity, you will write down the monsters and NPCs that you want to use for your dungeon.

Open the workbook that you created in chapter 2.

During this exercise, will draw from the monsters you ideated in the last activity, writing out their stats fully. You will also build on the work you did defining dungeon denizens in chapter 3. If you want, take a few moments to reacquaint yourself with the dungeon worksheet on page 3. Also, reacquaint yourself with the “Reasons to Fight” and “Reasons to Talk” on your checklist on page 5.

Navigate to page 8: Dungeon Denizens. Write your answers down here.

At this point, we are still writing in pencil, not ink. There is a space for location on this worksheet. If you have an idea about where you think they’ll live on the map, go ahead and jot it down. We’ll finalize if you want to place these characters on the map or on the random encounter table in chapters 11-13.

If you’re interested in seeing my work for some monsters and characters for His Majesty the Worm, check it out here.

My dungeon denizens are here. My goals with my dungeon are to try to put some fresh spins and reskins on very common dungeon creatures. Even going so far as to reskin a spiked-pit traps as the immobile but clawing hands of the dead.

Step 1. Establish creatures

Using your previous work, choose three creatures (monsters, animals, automatons, non-thinking antagonists, etc.) to use in your dungeon.

- Choose one pawn: a common, low-level antagonist.

- Choose one elite: a monster with a special ability, trick, or competency.

- Choose another elite.

Step 2. Establish non-player characters

Using your previous work, choose three characters to use in your dungeon. Consider having a variety of dungeon people, social puzzles, and weird little freaks.

Step 3. Fill out the detailsDraw the rest of the owl

Then, for each creature and character, fill out the following details:

- Write a name for each denizen.

- Write the room number they will be encountered. If they roam the dungeon by default, write “Wandering.” (This detail can be changed later.)

- Select or invent a main personality trait or task the denizen is doing by default.

- Write the stats you need to reference at the table as the GM for this denizen.

At the end of this step, you should have three creatures and three NPCs ready to use for your dungeon!

My completed list of dungeon denizens looks like this:

Further reading

How do I reskin monsters to make new ones?

The Cocktail Codex makes the bold claim that there are only six cocktails, with all recipes able to be linked at least tangentially to one of these root recipes. So a Martini is defined by the relationship between spirit (gin) and aromatised wine (vermouth), so a Manhattan is simply a relative that uses whiskey instead of gin, sweet vermouth in place of dry, and bitters added for seasoning the added sweetness.

…

Can we do the same for Monsters?

In Monster Design from Classics, the game designer Chris McDowall makes the bold claim that you can mix up new monsters by varying a classic recipe in the same way you can mix up a new cocktail. Every creature in a big monster manual is just a variation of one of the core mechanical recipes: an ogre is a strong and stupid humanoid monster; a zombie is a weak and stupid humanoid monster. Despite their differences, you can think of ogres and zombies as variations on a recipe.

How do I make sure I maintain a good variety of monsters?

What makes foes distinctive is either their place in the game world (how the players can interact with them as NPCs), their descriptions, and sometimes unique abilities or ‘tricks’ that make combat with them interesting.

In Monster Design and Necessity, Gus L. lays out an interesting categorization of “A) Weak intelligent Combatants B) Normal Intelligent Combatants C) Very Weak Animals” and different special “tricks” that help think about old-school beasties. By categorizing the different monsters of your theme, you can ensure you have a enough variety to keep things interesting.

How do I make NPCs with cool “wants” and “gives”?

For my money, the most important thing is that NPCs be extremely on their bullshit. This means:

- They have something they are very interested in.

- They have something that is of interest or value to you.

- They are not interested in you or your goals.

In Zelda-Style NPC Personalities, Alex from ToDistantLands discusses what makes NPCs in Zelda games so unique: they are extremely into their own BS! Use Zelda-style character creation to help build out your NPCs and factions.

How can I make more compelling and realistic NPCs?

When I say “short story,” I’m talking about concise prose fiction. It is narrative without fat. It is “about” a singular theme, idea, twist, mood, or moral.

In “Every NPC is an Unfinished Short Story,” Will Savino makes the claim that…well…I think you get it.

OK, that’s too heavy. Are there simple tips and tricks for making an NPC?

To me, an NPC is essentially the same thing as a trap, puzzle, monster, or magic item. They are simply another asset in my toolbox for crafting obstacles and opportunities to challenge my players.

Dwiz at KnightattheOpera lays out a series of simple patterns he uses to create fun, gameable NPCs in his article People Are Problems: NPCs as Challenge Elements.

Do I have to talk in funny voices?

What’s more interesting? A game with exciting combat? Or a game with exciting combat AND tense negotiations?

When you can defeat a dragon with clever words or powerful weapons, you now have more strategies that the players can employ. Their toolbox is bigger, and so is the game.

No, you don’t have to talk in a funny voice. Arnold K. of Goblinpunch lays out some good rules for Handling Parley as an OSR referee to help think through the ways you can handle social “puzzles” at the table.

All spot art in this chapter (and this course!) by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

Being a billionaire must be insane. You can buy new teeth, new skin. All your chairs cost 20,000 dollars and weigh 2,000 pounds. Your life is just a series of your own preferences. In terms of cognitive impairment it’s probably like being kicked in the head by a horse every day - @Merman_Melville, posted on Twitter, Jan 24, 2019 ↩