Chapter 4: Creating the Map

Maps are an important tool that help GMs and players understand the space where the adventure takes place. It’s the simplest way to see at a glance all of the different rooms, the size of these different areas, the connections between them, the entrances and exits from each room, and so on. In this chapter, you’ll draw a simple map with 30 rooms.

Table of contents

- Setting the dungeon in your setting

- Entrances and connections

- Depth

- Interesting pathsTheory

- Scale and orientation

- Room numbers

- Caveat: This is not a drawing courseTools

- Activity: Draw your mapActivity

- Alternative Activity: Five 6-Room ClustersAlternate Activity

- Give your players the mapAdvanced Theory

- Further reading

Setting the dungeon in your setting

So far, we’ve been talking about this dungeon in a very isolated way. This has been to allow for the scope of this exercise. But it’s important to think about how your dungeon fits into your game world.

As a matter of course, consider the dungeon’s relationship to the rest of your campaign setting.

- Where is it?

- How do the players get there?

- Is its existence known?

- If it’s known, what keeps normal folks from going in?

- How do the players overcome this obstacle?

- If it’s unknown, how do the players find it?1

The Origins of the Underworld: In His Majesty the Worm, the first step to creating your campaign space—the Underworld—is to define the origins of the Underworld. In this course, we’re only making one dungeon. I’m assuming that, if you’re running His Majesty the Worm, you will have already done this step before you sit down to populate a dungeon. My dungeon will be written so as to be as agnostic about your answers to these questions about the Underworld’s origin as possible.

Entrances and connections

What is the entrance to your dungeon? Is there more than one? Are these secondary entrances known or hidden?

A hidden entrance to a dungeon can be a good reward for thorough exploration. This can allow the players to reenter the dungeon at a later time while bypassing a guardian or extracting treasure more efficiently. Chapter 6 discusses how to position these sorts of secrets in more detail.

Another thing to consider is if this dungeon is a single adventuring site (e.g., a day’s ride away, you will find a barrow ringed with a henge of stone—inside are twelve separate chambers, in which are entombed the First Kings) or is it a single level in a larger complex (e.g., the cellar of this building, like most buildings at street level in the city of Rain, go down into parts of the Old City—who knows how far all the tunnels go?).

If this dungeon is connected to other levels, what are these connections? Connections to deeper sections of a larger underworld complex might include:

- Stairs

- Tricky doors (one-way doors, hidden doors, alarm-trapped doors)

- Portals

- Elevators

- Shafts

- Rivers

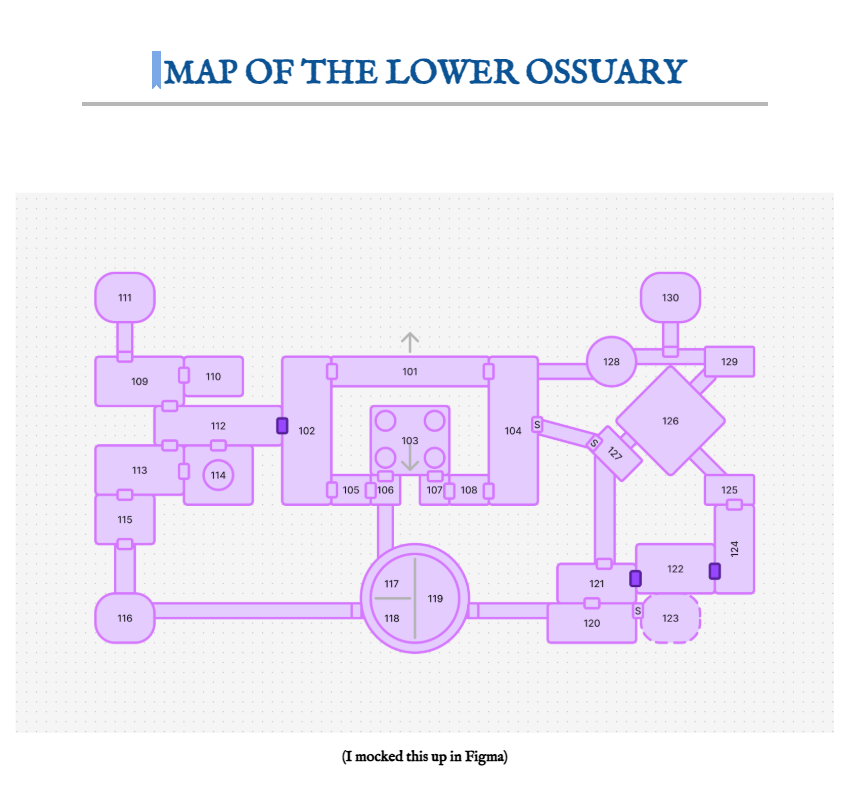

One of my goals while designing my dungeon is to create something that other Worm GMs can use in their Underworld. I hope that you can plug my dungeon, the Lower Ossuary, into your own game with minimal effort. To this end, my dungeon map will have connections to the surface and to a deeper level of the mythic underworld. If you want to use it simply as a single adventuring site, remove the stairs in room 103.

Choices in the first room

Entrances are often the dungeon’s first impression.

I want to take a moment to pause on the first room that you might draw: the entrance to the dungeon. At first thought it might not seem like it matters very much. Just draw a square, stairs leading down, maybe a door or hallway leading to the next dungeon room. But that is a quite boring first impression for your players who are hyped up to be playing a fantasy adventure game.

A primary element to dungeon entrances should be the immediate presence of a choice. As noted earlier, making impactful decisions is why people enjoy playing RPGs—so let’s give that to the players immediately. This can be as simple as choosing between an ornate red door to the east or a plain blue door with something carved on it to the west.

The second element of dungeon entrances is that their contents reinforce the themes of the dungeon. The two different colored doors might be connected to the two siblings who built the dungeon. A statue might depict the dungeons architect or contain an important phrase that is repeated later. (We’ll get to filling the contents of your dungeon in a later chapter, just highlighting it as an important consideration.)

Depth

In original D&D, the idea of dungeon levels would roughly correspond to a character level. The deeper the dungeon level, the more dangerous it was, so only a character of a sufficient level could be expected to meaningfully navigate its dangers.

Even at the most basic level, dungeons that are farther away from the civilized world are more difficult to access. It requires more resources like torches and rations to journey to reach these levels. When setting a dungeon at a deeper level, consider adding more difficult risks and more extravagant rewards as you stock this level.

If you are writing a single adventuring site, your dungeon is probably accessible to the outside world. Even so, you might place it far from civilization (a dungeon only accessible after a long journey to the North Pole) or not normally accessible by common people (the Forbidden City imperial complex, only accessible to the royal family and their servants). In this case, these dungeons have the additional risks implied by being “deeper levels.”2

If you are writing a single adventuring site, your dungeon is probably accessible to the outside world. Even so, you might place it far from civilization (a dungeon only accessible after a long journey to the North Pole) or not normally accessible by common people (the Forbidden City imperial complex, only accessible to the royal family and their servants). In this case, these dungeons have the additional risks implied by being “deeper levels.”2

Interesting pathsTheory

If choice is the interesting part of dungeon crawling, we’ll need to ensure that there’s lots of interesting choices in the map itself.

A map that is a straight line, from room 1 to room 30, wouldn’t be very interesting! Interesting dungeons have different paths to explore: some that look promising, some that look dangerous, some that hint at loot, and so on.

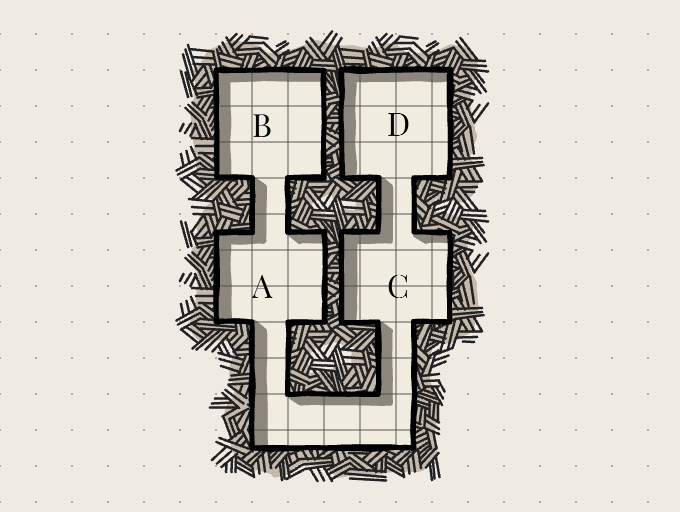

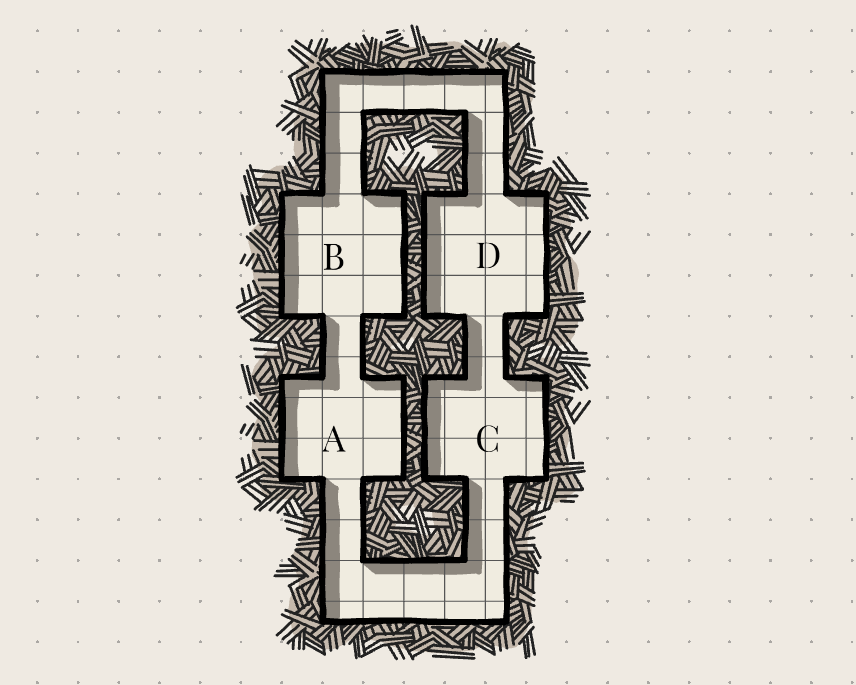

Linear dungeon

Consider this simple dungeon map. An issue with this map is that to get to rooms B and D, you always have to pass through rooms A and C. Assuming you need to explore rooms B and D to complete the dungeon, the players can’t make any real choices here.

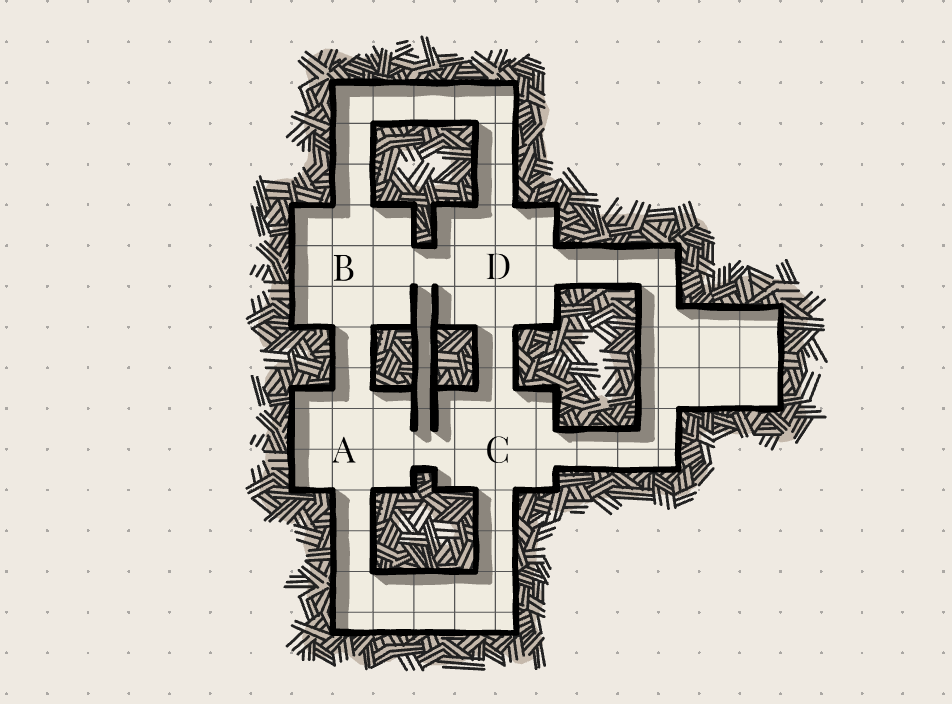

Adding loops

Now, consider that we add another point of connection in the map. Players can now approach room B from either A or D.

From here, each new loop you add creates an exponential effect. More loops allow for more and more variations of potential paths through the dungeon.

Ensuring that your dungeon maps have loops is often called “Jaquaysing the dungeon,” in honor of the game designer Jennell Jaquays and the loops of her famous dungeon Caverns of Thracia (Judges Guild, 1979).

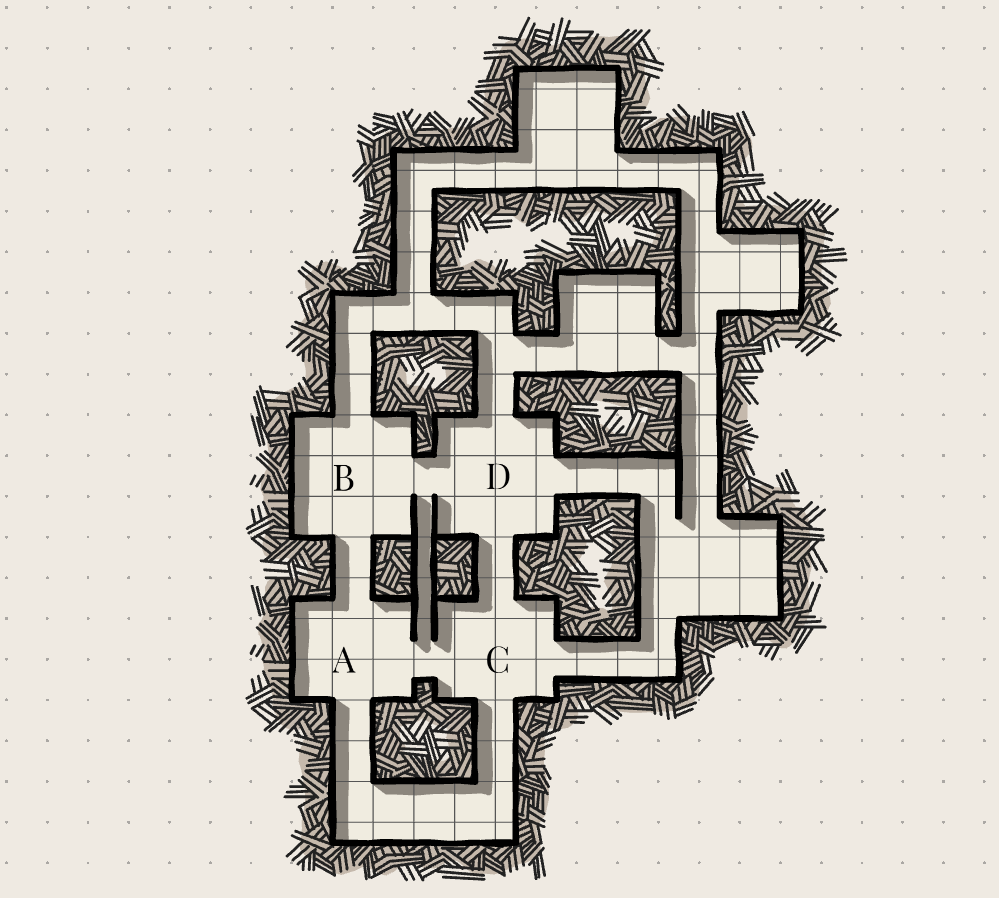

Adding loops within loops

As you add new connections, you add new loops. Each loop opens up new pathways—potential ways for players to go backwards and forwards, running from monster encounters, leading them into dangerous rooms, looping back around behind them, shoving spikes into the doors to stop monsters from retreating, etc. These little plans are lots of fun, and only available when there’s lots of pathways that are available for enterprising players.

An important part of creating multiple pathways is broadcasting the different potential choices down each path. Making informed decisions is the fun part of the game. For each path you add, broadcast information to your players by adding smells, sounds, graffiti, and other clues that hint at what the players may find by pursuing those paths.

The non-linearity of the maps and expanse of content works to your advantage. Because there are many ways to go, you can afford to get “stuck” on a challenge. In linear dungeons, a puzzle that blocks the way forward can cause hours of frustration for player and GM alike. In non-linear dungeons, it’s not a problem. The players can leave and continue to play and explore. If someone has an insight or if a key is later discovered that fits that puzzle’s lock, they can return. Also, because of the nature of the medium, there should be many ways to solve any puzzle. You’re not just trying to guess what the game wants you to do—you’re finding logical solutions that work within the context of the game world.

A Thracian Ruin: Loops are not the only thing Jennell Jaquays contributed to dungeon design. In Gus L.’s informative post on The Caverns of Thracia, he points out that a big piece of what makes the dungeon special is its strong sense of history and lived-in feel. This is a sometimes difficult trick to perfect so don’t worry if your dungeon doesn’t immediately read like one of the greats, but it is an aspect that helps a modern reader appreciate what was accomplished.

Scale and orientation

Scale and orientation are practical considerations. Some games have different assumptions here (is a square 5’ or 10’?). For the purposes of this course, we’ll keep things simple. The top of the map is north. Each square represents a space 10 feet by 10 feet. This allows you to make basic descriptions when you look at the map, e.g., “The hallway is 10 squares long, so that’s 100 feet long. At the end of the hallway, there’s a door on both the east and west walls.”

Room numbers

I key maps of a multi-dungeon underworld with two designator digits. The first digits correspond to the level (Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, etc.) and the second digits correspond to the room itself. The level number corresponds to the depth of the dungeon (the uppermost dungeon level is Level 1). In practice, this usually looks like a three-digit code: 502 (Level 5, Room 2), 213 (Level 2, Room 13), etc.

This is just one method. In truth, any numbering system that works for you will be good to use here. The important thing is that your room keys are easy to understand for you.

Caveat: This is not a drawing courseTools

Some GMs balk at the simplicity of squares and hallways, and want an end product at the table that’s more aesthetically compelling. For me and my gaming group, simple is fine! If you feel differently, here are some resources for you:

First, there are many beautiful maps created by professional cartographers that are available online for both personal and commercial use. Instead of drawing your own simple map, borrow a map from these talented creators!

Tim Harten’s Friday Freebie Maps

Tim Harten is one example of the many talented cartographers that contribute maps to the RPG community. Their Friday Freebie Maps are a great resource to use if you’re looking for a dungeon level to start from and stat out.

Alternatively, you might use randomized dungeon generators to create a few maps programmatically. You can keep generating layouts until you find one that appeals to your aesthetics and sensibilities.

Watabou’s One Page Dungeon

Watabou’s Dungeon Generator will quickly create a map with a randomized layout. Make about 20 of these and grab your favorite.

There is also dungeon cartography software that creates compelling art exactly to your design specifications.

Dungeon Scrawl

Dungeon Scrawl is a web-based cartography program that lets you mock up a nice looking map quickly. It’s great for small scale adventure sites, like the 30-room dungeon we’re making during this course.

Finally, if you prefer to draw your own map but want to uplevel your cartography skills, there are links to some helpful resources in the Further reading section of this chapter.

If you would prefer to use a pre-generated map, just skim this chapter’s activities.

Activity: Draw your mapActivity

In this activity, you’ll put pen to paper and draw a map for your dungeon. You’ll start by defining shapes for rooms. Then, you’ll create connections between those rooms. Lastly, you’ll use a numbering convention to key your map.

If you want to see my version of the workbook with this activity complete, check it out here.

Step 1: Prepare your grid paper

Decide if you want to use digital tools (like Photoshop, Microsoft Paint, or anything else) or analog tools (pen and paper) to draw your map. Then, prepare your drawing space.

If you want to use digital tools to draw your map:

- Download an image of graph paper here

- Open grid-paper.png in the drawing software of your choice

Alternatively, go old school:

If you want to use pen and paper to draw your dungeon, print page 4 of the Designing Dungeons Workbook (or, you know, just use a sheet of paper that you have).

Step 2: Draw the entrance

Consider what the dungeon’s entrance should look like. Be inspired by your dungeon’s themes and background. Imagine a gate into adventure.

- Draw a square to represent the entrance

- Mark the square with an up arrow to designate it as the entrance

- Draw 2-3 rooms immediately adjacent from the entrance to give your players choices as soon as they enter

Step 3: Draw shapes for half of the rooms

The shape of your rooms will be determined by the structures defined in chapter 3. Are they rough, naturalistic stone walls? Is it built by human hands? Built by inhuman hands?

In this step, you will draw about half of your rooms. Use different shapes to represent different areas: draw squares to represent rooms, circles for towers, cloud-shapes for forested spaces, etc. Draw some spaces clustered together as contiguous rooms. As you draw, leave some spaces between the different clusters of rooms.

Draw shapes to represent different areas

- Draw a variety of large rooms and small rooms

- Draw about 15 rooms

Step 4: Draw pathways

Dungeons should not be linear. Remember, a game is fun because it’s a series of choices. If there’s only one path through the dungeon, you’re not allowing your players to make choices.

Draw ~15 more rooms, paths, and hallways that form connections between the rooms you drew

- Make sure there are shortcuts

- Make sure there are chokepoints

- Make sure there are loops

As you draw, clean up your map, redrawing sections until you are satisfied with the spaces and the connections between them.

At the end of this step, you should have ~30 rooms.

Step 5: Create connections

Consider if this dungeon should be a stand-alone complex or part of a larger dungeon.

- If you decided to have multiple entrances, designate these extra entrances by drawing an up arrow

- If you decided the dungeon would have connections with other dungeon levels, designate these exits by drawing a down arrow out of the room

Step 6: Add doors and secret doors

- Draw small squares (or tick marks) to represent doors between rooms

- If two rooms aren’t connected with a physical door, leave that space blank

- Designate at least one door as a secret door by drawing an S near the door

- Designate at least one door as a special door by coloring the square in completely. (We’ll decide what this means, exactly, in a later chapter.)

Step 7: Key the map

In this example, we’re going to call this dungeon Level 1, so we’re going to key all our rooms as “1xx.”

Don’t key short hallways. Consider adding a key to longer hallways or pathways as they can be interesting spaces in their own right.

- Starting at your primary entrance, key that room 101 (the first room of Level 1)

- Working left to right, top to bottom, key each area the next sequential number

- The goal is to have sequential numbers mostly near each other

At the end of this step, you should have 30 rooms labeled 101 to 130.

If you drew your map using digital tools, replace the image of grid paper on page 4 of the Designing Dungeons Workbook with your finalized map. Rename “Map of Dungeon” with the name of your dungeon level.

In future chapters, you can redraw, correct, renumber, and just recreate the map in any way you need to accommodate the things you will discover and define about the dungeon.

Writing to constraints can also improve your writing. If you wish, use the map you made today and, when you wonder why something is in a particular configuration, your answer might give the dungeon a new level of depth, realism, or weirdness that improves the experience.

My completed map looks like this:

Alternative Activity: Five 6-Room ClustersAlternate Activity

If you’re making a dungeon using B/X procedures, consider this alternate activity instead.

One helpful method is to break a 30-room dungeon down into five 6-room clusters. I keep coming back to the number 6 because it is also the total number of outcomes in the original B/X stocking procedure and allows each room to be assigned to one of those outcomes:

- monster

- monster + treasure

- trap (2-in-6 having treasure)

- 2x empty rooms (1-in-6 having treasure)

- a room that is “special”

The theme of these clusters can be dictated in a couple of ways.

The first might be to theme it naturalistically by using one room to inform the adjoining rooms. For instance if you have a large kitchen, you could add a dining room, pantry, small office, linen closet, and staff area.

The second could be more factional, by using a faction head or a random “monster + treasure” result. So the other 5 rooms could be variations on that monster or give clues to its past doings. A goblin king would also have a room with: goblin jesters, favorite pet scorpions, trapped food stuff, bedroom of stable hay (treasure underneath), and shredded library (empty).

A third way might be thematically by reviewing some of your brainstorming ideas and building off that. A fountain that spawns flying goldfish might also have a room with a goblin flying fish-fry, a flying fish colony, a dungeon spider catching them, and maybe a bandit trying to reach a special green one by fishing on the ceiling (using a line with a ring of levitation tied on it).

So which method might you use? It depends on whether you are drawing your map or using one from another source. In the former case, it might be helpful to use the first method since you will need to draw every room and control how they look. While in the latter case, methods 2 and 3 might be more suitable since you don’t have control over the rooms or their shape.

You can see my copy of the completed map here!

Give your players the mapAdvanced Theory

Hey, this section is me talking about a technique that works well for me. Feel free to skip if this is not your cup of tea.

I advocate giving players an in-character copy of the dungeon map. The player-facing map should not contain any information about the contents of dungeon rooms. However, each

map should:

- Show the basic outline of the rooms;

- Show the paths through the dungeon; and

- Be keyed, with each room having a different number.

Although the players have some basic information about a room’s shape and obvious exits, there is still a lot of exploration to be had! What do the rooms contain? How do you safely navigate the rooms’ puzzles, monsters, and traps? What secrets and hidden features are not on the map (yet)? What a room contains is a much more interesting thing than the basic shape of a room.3

If you decide to give your players a copy of your map (which I certainly will!), you will clean up the final version of your map for player consumption in a later chapter. First, let’s just focus on finishing your dungeon.

Wait, why give the players a copy of the map?

There are many advantages.

Describing an environment in feet and orientation is a verbal puzzle that is harder for a person at the table than it would be for a person in that actual space. Look up a picture of a big cathedral, like Notre Dame. You can see that space and understand it pretty easily. Now imagine trying to say out loud all the dimensions so someone can make a good map of it.

In practice, asking players to map has always felt like a negative experience to me. When the players make mistakes, you have two options:

- Correct them: “On the north wall, there’s two exits. No, the left exit is farther away. No, not like that. Here, let me just draw it for you.” This takes up GM time and mental resources, and is frustrating for the mapper.

- Don’t correct them: “On the north wall, there’s two exits.” Later, the map doesn’t work. The hallway past the left exit can’t physically exist in space because the original map was drawn badly. This is frustrating for the players because they are now confused in a way that their characters wouldn’t be. A character in the world would not have made the mistake in mapping that the player makes at the table.

When running games, letting the players manage the map means that the GM is freed up to do other things. They say: We’re going to room 101. The GM just has to CTRL+F “101” into their game document and read the description. The players can look at a map and see the obvious exits. The GM doesn’t have to list them. The players can make informed decisions about navigating the dungeon: there’s 3 rooms between 101 and 105, which they think is where they need to go. Having information to make decisions is the fun part of the game.

Further reading

How can I learn to draw dungeons?

Here are two cartography tutorials if you’re looking to uplevel your skills in this department:

- Path’s Peculiar’s How to Draw a Basic Dungeon Map Tutorial

- JP Coovert “How to Draw and Design a Dungeon Map”

What’s an easy way to create an interesting map?

In Bite Sized Dungeons, Marcia of Traverse Fantasy talks through using the “Six 5-room cluster” method of dungeon design using little polygons. She even provides a workbook for it! Check it out if you’re using the alternate activity.

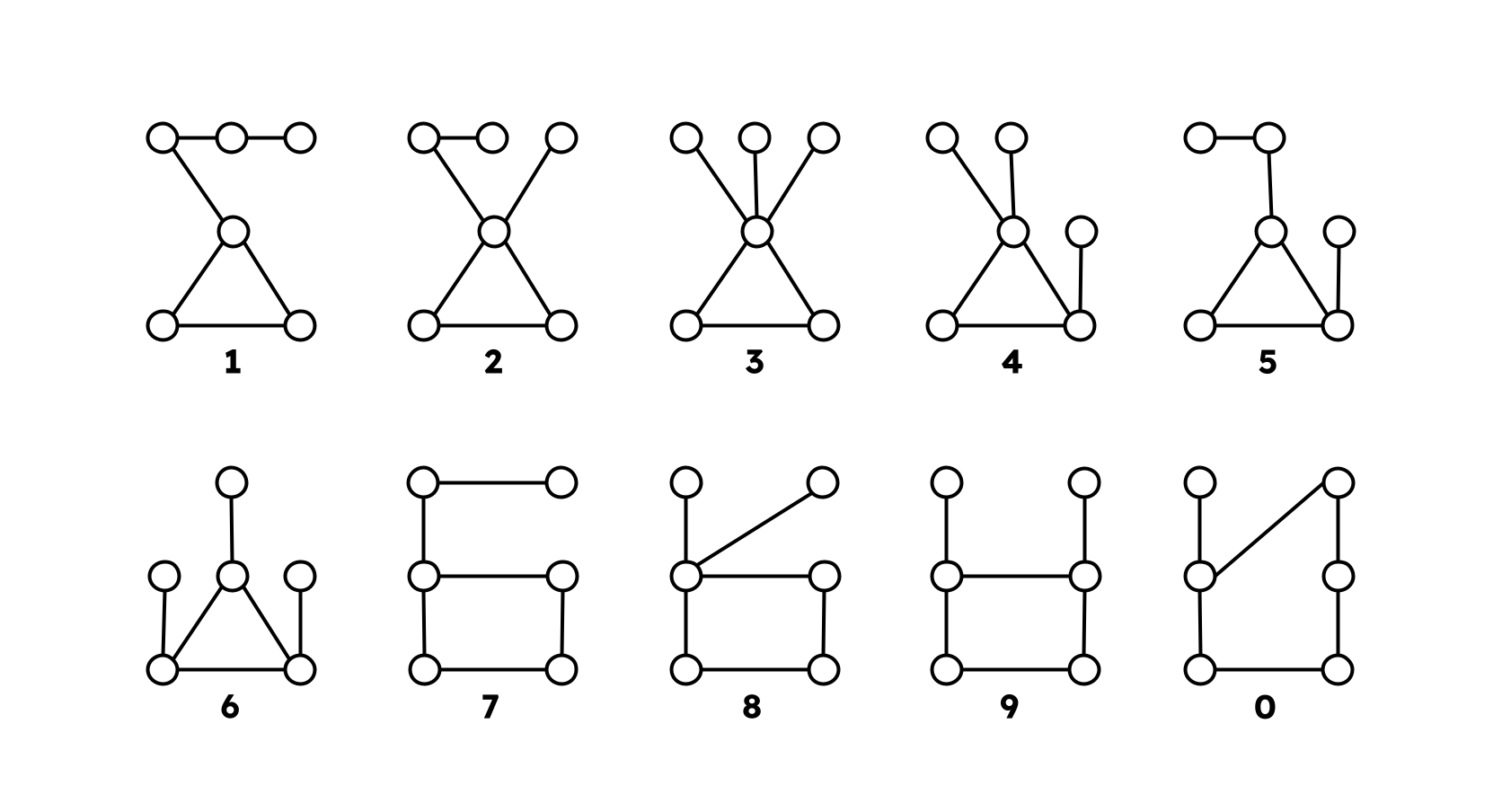

Is there a good way to key my map with icons?

The early D&D maps were rich with icons for all sorts of different things; each different trap type had its own little symbol. That might be a bit overkill, but icons can be fun to use and give your map some zhuzh. Game Maker’s Toolkit has a Patreon post analyzing Zelda dungeons, which provides a very handy dungeon graphing system. Check it out here!

Why is making looping paths in dungeons sometimes called “Jacquaysing”?

Nickoten provides a little context and framing around the common term “Jacquaysing” (and unwelcome alternatives) in their article: How Jennell Jacquays Evolved Dungeon Design

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩