Chapter 11: Keying room descriptions (Part 1)

Writing to the checklist

In this chapter, you’ll begin keying your rooms using the content that you’ve accumulated from the previous exercises. Josh and Warren both provide different approaches to building out your dungeon:

My approach will focus on the content of the dungeon checklist. You’ll write about 15 rooms during these activities. The next chapter will build out additional rooms until you get to our goal of 30 rooms.

My alternate activity creates six-room clusters aligned to the classic dungeon room types of B/X D&D. Check out my approach here.

Table of contents

- Gather your materialsActivity

- Let’s write some roomsActivity

- Entrance

- Clue room x 2Reason to Explore

- Monster lairReason to Fight

- More monstersReason to Fight

- Interesting featureReason to Experiment

- Trap x 2Reason to be SurprisedReason to Experiment

- “Empty” roomReason to Breathe Easy

- NPCReason to Talk

- Tricky doorReason to Experiment

- Bounty and Rumors x 2Reason to Explore

- Dungeon Lord’s lairReason to Flee

- Josh’s dungeon: The Lower Ossuary Resource

- Alternative Activity: Writing A Six-Room ClusterAlternate Activity

- Warren’s dungeon: Barrow House of the Headless Mage Resource

- Further reading

Gather your materialsActivity

Much of our work over the previous ten chapters was to get us ready to do this task, giving us lots of grist to mill.  Open the workbook that you created in chapter 2. Then, go ahead and open another copy in a second tab. By having two copies open, you can reference your past work while keying your rooms.

Open the workbook that you created in chapter 2. Then, go ahead and open another copy in a second tab. By having two copies open, you can reference your past work while keying your rooms.

Reacquaint yourself with the map you drew on page 4. It’s helpful to have the sense of space in your head as you begin writing.

As you write, glance at the map and choose a room that makes intuitive sense to you for where to put that element. You won’t go room by room, 101 to 130; jump around.1

As you write room descriptions, you’ll learn more about the dungeon. You can change the map if you want. Alternatively, you can use the map as a constraint. When something doesn’t seem to make sense, ask yourself “Why would it be this way, actually?” The answers you come up with will probably be better than what you had originally.

As a refresher, here is the dungeon checklist that we discussed in chapter 5:

- A reason to explore

- A reason to talk

- A reason to flee

- A reason to breathe easy

- A reason to experiment

- A reason to fight

- A reason to be surprised

- A reason to return

Today’s work will focus on implementing your ideas for these items.

As you write, use the principles of good keying from the last chapter. But remember that you’re just writing for yourself! Give your future self what you need, and don’t worry about making it perfect.

“How I write an Adventure,” Arnold K.

“This process isn’t linear, it’s iterative. You keep going over your dungeon until it feels fleshed out. […] Try to come up with a reason why each part of the dungeon exists. Try to come up with reasons why you should remove it.

Cut away all the parts that aren’t awesome. It’s better to have a small, excellent dungeon [than] it is to have a bloated, generic megadungeon. […] Be aggressive in your deletions. Remember that amputated content can go back into your slush pile.”

Let’s write some roomsActivity

This section details how I approach writing a new dungeon. Warren’s approach is below.

Entrance

Key the entrance to the dungeon. Put something interesting to interact with in this room. Give the players some choices to make right away.

Make sure to add details that help establish the theme and history of your dungeon.

What does this entrance tell the players about what to expect in the dungeon?

Is there anything that guards the entrance? A sentinel monster? A trap? A puzzle?

Clue room x 2Reason to Explore

Key the next two rooms connected to the entrance.

In each room, put a single instance of something you plan on using deeper into the dungeon. If you have a particular type of monster that makes a home here, put a single instance of it in one room. If you imagine your dungeon is full of traps, put one sprung trap in one room.

In both rooms, add further details that establish the theme and history of your dungeon.

These rooms establish what the players can expect going forward. Signpost dangers more obviously in these rooms. Teach players what to look for. Introduce them to concepts one at a time.

Monster lairReason to Fight

Refer to your Dungeon Denizens list on page 8 of your workbook. Key a room where one of your monsters makes their home.

Spend some of your treasure budget in this room. Braving the monster should have some reward.

More monstersReason to Fight

Key another room where a monster is likely to be encountered. This might not be their permanent lair, but a room that has some use for them and makes sense in the context of your dungeon theme.

Interesting featureReason to Experiment

Put something interesting to interact with in one room.

The purpose of this feature should fit the theme of your dungeon, be fantastic, and optimally be dangerous but useful if used correctly. Refer to dungeon features in chapter 6 if you need inspiration.

Trap x 2Reason to be SurprisedReason to Experiment

Key two rooms with a trap or hazard. Use the ideas you generated in the Traps and Secrets section on page 6 of your workbook.

Decide whether each trap will be:

- Hidden, with a clue that hints at its existence

- Obvious, but with no easy way to bypass it

You might spend some of your treasure budget here. Alternatively, the hazard can provide a speedbump to some reward or dungeon denizen’s lair deeper into the dungeon.

Remember, the deadlier the trap, the easier it needs to be to see. Broadcast danger generously. The interesting part is “how do we get past the trap?” not “is there a trap in this room?”.

“Empty” roomReason to Breathe Easy

Key a normal, non-dangerous room that makes sense in the context of the rooms you’ve established thus far.

Remember, an empty room isn’t a featureless white room. It’s an opportunity to showcase lore, provide a resting space, and hint at traps or secrets.

NPCReason to Talk

Key a room that houses one of the non-player characters you wrote about in your Dungeon Denizens list on page 8 of your workbook.

Who will it be? A dungeon person, a social puzzle, a weird little freak?

Hidden featureReason to be Surprised

You might spend some of your treasure budget here. Alternatively, the hidden feature can occlude a clue, a hint, important lore, or something else.

Don’t block progress with puzzles

Remember not to block all forward progress with hidden features! If players can’t find the feature, they should still be able to move forward in the dungeon in another way.

Tricky doorReason to Experiment

Key a room that’s protected by a secret door or special door. Use the ideas you generated in the Traps and Secrets section on page 6 of your workbook.

Spend some of your treasure budget in this room. The tricky door should be guarding something worth guarding.

Bounty and Rumors x 2Reason to Explore

Reread Hooks, Rumors, and Bounties on page 29 of your workbook. Select two rumors or bounties to focus on for now. Put these details in a room that you have already keyed or key a new room to house this content.

A bounty/rumor can be a reward for overcoming a tricky door, trap, or monster.

Dungeon Lord’s lairReason to Flee

If you decided to include a dungeon lord in your game, key a room that houses the boss battle that you wrote about in your Dungeon Lord Encounter on page 9 of your workbook.

Don’t forget to put the monster’s hoard in this room or a nearby room. The rewards can also be related to a bounty or rumor!

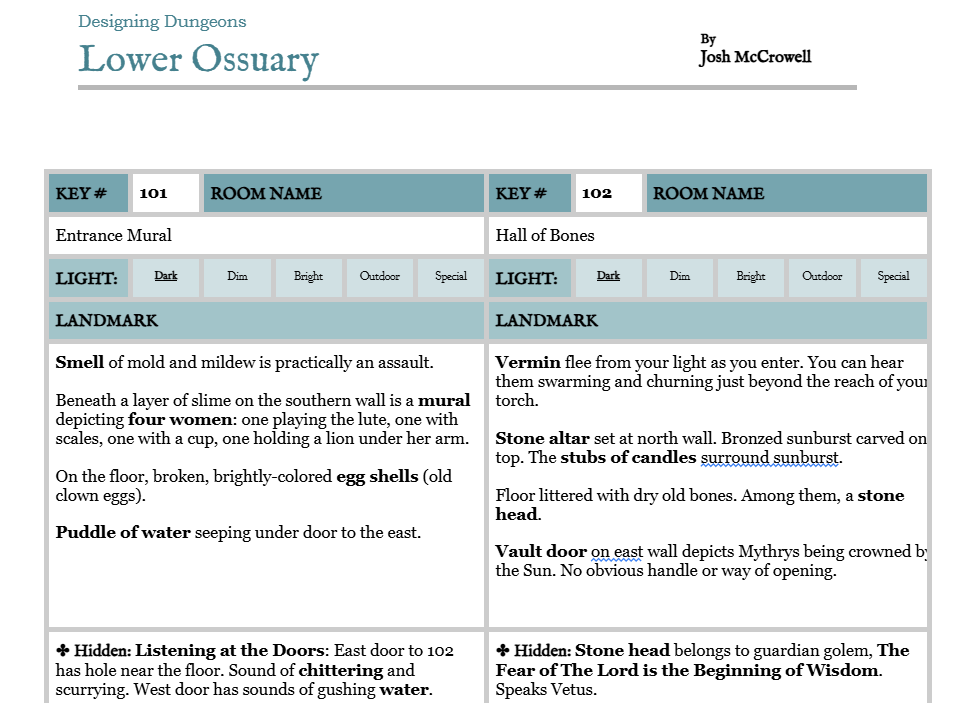

Josh’s dungeon: The Lower Ossuary Resource

If you want to see how I’ve been answering these questions, check out my dungeon workbook, here.

As I’ve been writing, I’ve left notes on some rooms where I had a germ of an idea that I want to build out. These will be fully fleshed out in chapter 12.

Alternative Activity: Writing A Six-Room ClusterAlternate Activity

Here’s where Josh and I differ a bit in our processes for actually building out content. I prefer to think of rooms in terms of the types laid out by original D&D. I suggested we make a 30-room dungeon to give an equal spread to these room types. Here is my alternate activity!

I want to look back at chapter 4 where we discussed breaking up your 30-room dungeon into five separate six-room clusters. We will stock this cluster using the B/X stocking method of monster, monsters + treasure, trap (2:6 treasure), empty rooms x 2 (1:6 treasure), and a special room.

In chapter 4, I also suggested that you could complete each cluster by using a naturalistic theme, a factional theme, or a theme based on a dungeon element like a monster or treasure. Since I drew this map and each area already has a function in mind, I am going to show you how I designed the first six rooms of my dungeon as a “naturalistic” cluster.

The premise

My dungeon idea is exploring the house of a wizard of middling talent who was hideously transformed due to a magical accident. Therefore, many areas include mundane spaces that have been “dungeonized” due to the magical accident. I started with the idea that the wizard might have mundane spaces at the front of the house to entertain guests and not have the front door immediately open into the laboratory. I also knew I wanted the first room to provide choices and give the players a clue about the dungeon, which, as we’ve discussed previously, are qualities of a good entrance.

For subsequent rooms, I reasoned there would be a sitting room and a dining room since the wizard would want to entertain. If we have a dining room, then there needs to be a kitchen. And if you have a kitchen, then you need cooks, so we need servants quarters. Finally, the mage bought things with golden goose eggs, so I figured this guy would have guards—let’s add a guard room. That’s six rooms total. And since rules are made to be broken, I added a seventh room: guest rooms because maybe people stay overnight (mostly willfully) instead of going to the town nearby.

Here’s my first cluster:

- Foyer (Special)

- Guard Room (Empty, Treasure Hidden)

- Fireplace (Monster)

- Dining Room (Trap)

- Kitchen (Empty, Treasure Hidden)

- Servants’ Quarters (Monster, Treasure)

- Guest Quarters (Special)

FoyerSpecial

My goal here is to have a room where several choices can be made. So let’s start with the “special” stocking result.

By the west wall, a pool of silvery water reflects not the room it’s in, but another room in the dungeon. Jumping in teleports a PC to this new location, but only one-way. A door in the east wall is locked (giving thieves an early chance to shine) but has a little window to provide more information on why it could be worth the trouble. To the south, an archway extends into another room. Finally an open hallway extends to the south.

Guard RoomEmpty, Treasure Hidden

Since we’re going to the trouble to lock a door, let’s make sure there is something good behind it. I am a big proponent of one-use magic items both to provide a problem solving tool and because magic is a big part of fantasy adventure games. So in this room I hid a potion of diminution in a mouse hole—cheesy, huh? This potion shrinks a PC or potential enemy and therefore is far more interesting than a potion that simply gives a mechanical bonus or does direct damage. Since I also have a room later in the dungeon where something has grown unusually large, it’s also a direct solution for it.

FireplaceMonster

I envisioned this room as a sitting room dominated by a fireplace. The monster I placed here was a trapdoor spider because of the monster’s false door ability, but also because it is possible to talk to it. The talking is an important part because, with low-level adventures it’s not hard to kill the PCs outright at the beginning. Talking and negotiating encourages the sorta PC:Dungeon interactions to lead to novel, humorous lateral thinking that makes RPGs sing.

The east door I decided to lock again to give thieves a task, but it’s also an immediate use for the potion of diminution. This is also the front part of the “house” and the most public facing so locked doors make sense to me.

A third route is provided in the chimney of the fireplace that leads through a large crack to the kitchen—but only halfling sized. Again, the idea is for the party to have options but party composition matters in the ability to make those options viable.

Woodland Dining RoomTrap

With this adventure, I tried to think of a couple of alternatives to the classic spiked pit trap. Since a magical explosion happened, all sorts of bizarre environmental effects can happen. Let’s invert the pit trap to be falling spikes, but in this case it’s silverware floating at the ceiling due to magic forces. Unlocked door to the kitchen, but another locked door to the south.

Like before, I have a small window so PCs can see that the locked door seemingly leads to an autumn forest. The window allows the PCs to gain information, which is more interesting.

KitchenEmpty, Treasure Hidden

If you have a dining room, you gotta have some place the food is coming from.

Hidden doesn’t have to be overly difficult; here, it just means they need to look in the oven and they find a golden egg (500sp). Again, like the silverware-turned-trap, mechanically its no different than a pile of gold coins, but the novel presentation can be delightful. The golden egg also ties into a central rumor, “Find the golden goose,” so its early encouragement, hopefully drawing the players further into the dungeon. Also players might try to hatch it.

Servants’ QuartersMonster, Treasure

And if you have a dining room and kitchen, then someone has to staff it. And what happened to those people during this explosion?

This is a pretty standard encounter, both monsters are zombies which lose initiatives but pack a punch (1d8 dmg). But, again, made a little fresh by the description which forms a vignette. Additionally, one ambling corpse is related to a second rumor that starts the adventure: “What happened to the men that went into the dungeon?”

Guest QuartersSpecial

Finally, I wanted to throw in this last room which I felt rounds out this cluster even if it breaks the six-room pattern. I thought the barrow-mage might have a place for guests to sleep overnight.

Each bedroom is enchanted with illusions. Both entrances to this area are locked, but a window in the doors hopefully entices the players. I didn’t want to place more treasure so I figure a potential NPC might be a good fit. This NPC could link to another campaign or simply be a level 1 magic-user (which could also function as a backup character).

So there you have it! A six (+1) room cluster designed around a naturalistic domestic space, but which includes a magic pool, locked doors, a magic potion, secret tunnels, golden eggs, flying knives, zombies, and a talking spider. Even just typing that out makes me feel pretty solid. It’s an interesting, choice-filled space that helps frame the adventure quickly.

Warren’s dungeon: Barrow House of the Headless Mage Resource

The dungeon I completed as part of this project can be found here.

Further reading

How many X is too much? What numbers should I be aiming for here?

In the sentence, “There are two doors. One is big and ornate, and the other is small and humble.” The storytelling doesn’t start with the description of the doors. It starts when you say there are two.

Use numbers to tell stories and change play. They can reward players or surprise them. They can make choices easy or complicated. When you know how much your design matters, you can control why.

In Design the Dungeon with Numbers Clayton discusses how numbers are patterns that help the design of your adventuring space. Well worth reading as you engage in what content you’ll keep and what you’ll cut.

What kind of dungeons exist, from small to large?

I want to propose 4 basic size classes of dungeon, divided partially by number of rooms but, more importantly, by the effect they have on the core gameplay loop of your campaign.

Dwiz at KnightAtTheOpera categorizes dungeons into four sizes: micro dungeons (~five room dungeons), medium dungeons (~30 rooms, what we’ve made during this course), dense megdungeons (dungeons that dominate an entire campaign), and sparse megadungeons (dungeon-shaped spaces that aren’t necessarily keyed). Worth checking out to better understand the range a dungeon can have and their impacts on play.

Bonus: If you’re interested in megadungeons (and who wouldn’t be?), Ben L.’s podcast Into the Megadungeon is a great exploration (ha) into this campaign structure, with interviews from game designers operating in this space.

Why is keying maps and writing room descriptions important?

Courtney Campbell at the Hack & Slash blog wrote a series of blog posts around a concept called the “Quantum Ogre”. The idea of the quantum ogre is an encounter that the GM scripts and happens no matter what. If the players go into room 101, they encounter the ogre. If they got into 102 instead, they still encounter the ogre. This sort of “illusionism” ultimately has a negative effect on player agency and robs the players of their ability to make meaningful choices (which is the whole point of the game). For players to meaningfully explore a dungeon space, you need to do this kind of prep and avoid quantum ogres.

What are other ways to cluster and group rooms?

If you’ve been digging Warren’s classic B/X procedure for stocking, there are other variations of this principle out there. MurkDice presents some alternate methods of DungeonStocking, which in turn links out to lots of related reading on the subject.

All spot art in this chapter (and this course!) by BertDrawsStuff. ↩