Chapter 10: Formatting room descriptions

Whew! You’ve been writing up a storm the past few chapters. Great job!

In the next chapter, we’ll begin the final work of populating each room with everything you’ve created so far. But first, we’ll use this chapter to talk through the most productive ways to format your writing for later use at the table.

Table of contents

- Writing usable text

- Axioms for good keying

- Activity: Spot the ErrorsActivity

- Activity: Format a room descriptionActivity

- Further reading

Writing usable text

As we’ve said before, this course is not about getting something ready for publication. This makes our task infinitely easier—we’re not communicating the ideas to an unknown person running your adventure without context. However, I often find that I am my own worst enemy: my memory is not good. I need to write somewhat verbosely so I can remember my intentions. Your needs may vary.

As you approach this chapter and its activity, write like you’re writing a love letter to your future self. Write what you need. Cut what you don’t.1

Basics

Each room has a number. We labeled our rooms using a three-digit code (101-130) in chapter 4. The room number makes it easy to read the map and find things in your Google Doc. The players move to room 103? Just CTRL+F 103 and you find your entry. It also lets you use the pro strategy of giving the map to the players.

Each room should also have a simple name. Names are easier for you to remember than the number. “Idol room.” “Waterfall.” “Under-scullery.” Glancing at the name lets you orient yourself to the contents of the room.

When keying a room, use progressive disclosure techniques. The format of the workbook matches the paradigm of landmark/hidden/secret, which we discussed in chapter 6.

Write a paragraph that describes everything immediately observable by adventurers first entering the room. This introductory paragraph is considered landmark information. It’s everything that’s obvious for players.

- In this paragraph, highlight anything that’s interactable in bold.

- Keep the descriptions short and punchy.

Next, write successive descriptions of everything you highlighted as interactable in the hidden text box.

Last, list everything that the players can discover by interacting with the hidden content in the secret text box.

“My Process,” Ben L. at Mazirian’s Garden

Here’s a dirty secret: I often literally use the first paragraph as read-aloud text to my players. … I think it works in my game because the descriptions in that first paragraph are very short and to the point. I try to make them evocative, employing turns of phrase and adjectives that paint a vivid picture where I can, but I keep them very brief. For the great majority of rooms that I don’t manage to fully key for a session, I just maybe just jot down a few words or a sentence for those that are near enough to where the players are exploring that they might come up in play.2

Here’s a simple example:

04 SHRINE TO THE SEA GOD: A large boat made of a rich dark wood, decorated in wild gold wave patterns dominates this room and designed as if sinking into the floor; wood crates (empty) are “floating” in the corners of the room; to the west is a blue soapstone sculpture depicting figure with a conch helmet, web hands and feet, riding a horse shaped wave, trident in right hand, pointing east with its left hand.

- Gold Waves _Monster_ Scintilipedes (6): HD 1-1 MV 20’ AC 10 Att 1 (1 dmg) Sp: Save v. Paralysis or be stuck in place due to undulating, hypnotic movements

- Blue Soapstone Sculpture: inscription “I point thee east to my realm and true treasure”

The purpose of writing descriptions in this format is to enhance your ability to parse what you need at the table while running the game. Big blocks of text can be difficult for your eye to follow. With a table full of players looking expectantly at you, you don’t want to skip salient details that are important for them to know. Progressively revealing information about what players can immediately see > what they can interact with > what they can discover lets you chunk this content up. Bolding words and phrases help you see at a glance what’s important to remember.

Axioms for good keying

Here are eight axioms for writing room descriptions that are clear and easy to reference during play.

First described, first keyed

Your bullet points should follow the same order as they were listed in the description. If the description of the room details a rug and an unlit chandelier, the bullet points should list the contents of the rug in the first bullet point and the unlit chandelier in the second bullet point. Your eye can count bolded terms and intuitively sequence them (up to about 7 or 8 terms).

Except monsters

The one exception to the rule above is monsters.

If you (like I do) use your basic room description as read-aloud text for your players, players will jump at the inclusion of monsters—-sometimes before you can even finish your description.

Consider these two scenarios:

Scenario 1:

GM: Galstaff, you enter the door to the north. Seven ogres squat around a fire. The room appears to be…

Player: Ogres! I rush in, blade ready, and attack.

GM: …okay, uh, you run into the…gaping chasm.

Player: Chasm! What chasm!

GM: Well you didn’t let me finish!

Scenario 2:

GM: Galstaff, you enter the door to the north. The room appears to be a natural cave, full of stalactites. A yawning chasm plunges in front of the door. On the other side of the pit, there is a simple kitchen with a fire. A huge cauldron is boiling something foul. Seven ogres squat around the fire. What do you do?

Player: Ogres! Across a pit! I shut the door, then ready my crossbow.

Even when a player doesn’t actually interrupt the description, once they have heard about a danger, their focus tends to be on the problem that needs to be solved. Their attention is divided; they stop actively listening.

Because of this fact, I list obvious dangers like monsters last in my introductory paragraphs. However, because I know that players will want to interact with those elements first, I list those monsters first in subsequent keying.

Engage all five senses

Paint pictures with your descriptions by engaging all five senses. Don’t leave out any salient details about things that players can see, hear, feel, or smell. Landmark sensory experiences can lead the players to hidden or secret content in the room.

Describe constants once, list exceptions

There’s no reason to repeat the same details over and over, room to room. In your Dungeon Worksheet (page 3 of your Designing Dungeons Workbook), list constants such as the general lighting levels, what the dungeon walls are constructed of, what the doors are made of, etc. When there are exceptions (a lit room in a generally dark dungeon), call that out in that room’s description.

You can also call out repetitions in the dungeon at the beginning of a keyed section: “NOTE: Rooms 5-10 all are made from a rust red stone which dwarves will know is not found on Urth but imported from Barsoom.” This, again, keeps the key tight and focused on important, interactable pieces.

Don’t tell the players what to feel

In the traditional division of labor, the GM describes the world around the PCs, and the players describe their characters’ reactions to it. This includes their characters’ emotional reactions! It can be off putting for players to be told that they’re feeling scared, happy, disgusted, etc. (unless those emotions are coming from a mind-controlling source).

When writing room descriptions, avoid suggesting how the room might make an adventurer feel. Leave those descriptions up to the players.

Focus on what the characters can know

Imagine if I described my basement like this:

A finished basement. Messy, mostly a storage room. Once, Josh’s friend Eli lived there for a few months. None of his possessions now remain.

This is not a very good dungeon description. How would the players know about the history of my basement and the dwellers now long since departed? Why is it worth spending word count on “Nothing here belongs to Eli”? What does any of this have to do with the task of exploring the room?

This is a silly illustration, but it’s easy to fall into the trap of talking about the history of a space in a way that’s divorced from what the players can actually act on.

Don’t fill your notes with histories that only you can know and the players can’t learn. Don’t waste words to describe things that are not unless there’s a good reason to do so. Focus on what the players can actually interact with.

Don’t assume the players’ pathing

Writing down terms like “the door to the right” will become confusing when the players enter that door and come back; it’s no longer on the right. Instead, use cardinal directions to orient items in space regardless of their position to the players.

Similarly, don’t fall into the habit of writing room descriptions that are only applicable the first time the players enter the room. If you imagine the players will interrupt the queen’s ritual in the throne room, you might focus your description on the ritual itself. Once the ritual is interrupted, you’ll find that you have few details on the throne room itself.

In general, write top-level descriptions of each room that are true regardless of the players’ context. Note exceptions, timed events, or special rules in subsequent paragraphs.

Let the map work for you

The map is your friend. Use it efficiently.

If something appears on the map, you don’t have to waste space describing it. For example, assuming each exit on the map is standard, you can avoid repetitive descriptions of all the doors in a room. Instead, only spend time describing an exit if it’s special—-like if it’s hidden or if the door has a special puzzle to open it.

Doors: Don’t make all doors in the dungeon a standard wooden one with a pull ring. Decorations on door often given a clue to what’s behind them and signal importance. An example is a dining room which might have a plain servants’ door to/from the kitchen, but grand double doors to/from the library or foyer. PCs deciding between the two can be interesting.

Similarly, if there are two types of rooms in your dungeon—say, natural caverns versus worked stone—-embed those details on the map itself. Use different borders to draw the different rooms. Then, you can reference the map to see what kind of room the players are in without listing the terrain type in each room description.

Again, describe constants once and list exceptions.

Activity: Spot the ErrorsActivity

Mysterious Chamber - a Nega-example by Gus L.

Our frequently-cited friend, Gus L., contributes this bad room description. Each misstep in keying is accompanied by his commentary. You can read more on his personal rules for keying here.

MYSTERIOUS CHAMBER3

Sorrow fills the party’s hearts4 as they enter the morbid chamber where dripping acidic ooze covers the floor, a product of the Blotomax the Sludge King’s past experiments with artificial life5. Yet the prospect of the golden treasure within6 lures them on. The dangerous sludge7 has eaten and obscured the room’s former use as a funeral shrine8. Statues of the nine great saints including Spindelta the Morning Bringer9 have lost their features like molten wax candles at the feast’s end10. If they manage to cross the dangerous sludge11 the party will discover a 30’ by 20’ chamber containing a 10’ square building, with a door on its north side, ringed by nine statutes. The chamber itself has several portals to the North, West, and Three more to the South12. Within the central chamber, once the shrine’s sacred heart13, the golden orb of King Mortax14 lies atop a skull. A relic of the nine saints, the golden skull was considered a priceless artifact of the ancient church, now lost and forgotten. The golden orb will fetch nine hundred gold persimmons in the dusty town of Trax15. Before the brave adventurers can claim their loot however, they must contend with the chanting ring of 12 sludge men who walk in a dolorous circle around the shrine, but may charge to attack16 anyone who enters, beating them with giant silver candlestick holders17. There is a secret trapdoor in this chamber that leads to the Fane of Flowers18.

Did you spot all the errors?

In addition to the mistakes on display, many things are missing from this badly-keyed chamber that make the key worse. Most notably any meaningful description of the space. All we get is sludge and an old shrine with melted statutes. Each element of the room could do with a few pieces of meaningful descriptions—not just the obviously lacking mechanical ones, but information that would allow the players to deduce that the room is a corrupted or desecrated shrine, information about the materials used and appearance of the room that would allow the referee to describe it better and respond to player questions.

Lastly there are no non-visual descriptions here—a sharp chemical smell could warn of the acid sludge, while the chanting mumbles of the sludgemen might allow a party to realize they were in the room prior to entry. Give these kinds of sensory information as well as what a location looks like.

Activity: Format a room descriptionActivity

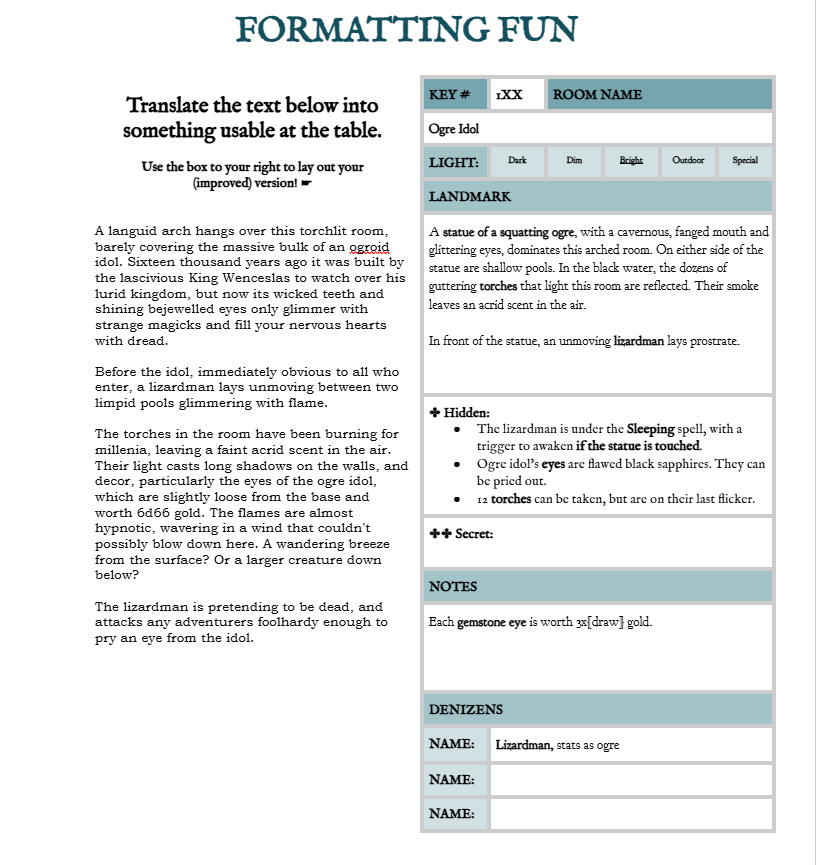

In this activity, you will rewrite a bad room description into something you’d actually like to use while running the game.

Open the workbook that you created in chapter 2. Navigate to page 11: Formatting Fun.

On this page, there’s a block of “bad” dungeon description text:

A languid arch hangs over this torchlit room, barely covering the massive bulk of an ogroid idol. Sixteen thousand years ago it was built by the lascivious King Wenceslas to watch over his lurid kingdom, but now its wicked teeth and shining bejewelled eyes only glimmer with strange magicks and fill your nervous hearts with dread.

Before the idol, immediately obvious to all who enter, a lizardman lays unmoving between two limpid pools glimmering with flame.

The torches in the room have been burning for millenia, leaving a faint acrid scent in the air. Their light casts long shadows on the walls, and decor, particularly the eyes of the ogre idol, which are slightly loose from the base and worth 6d66 gold. The flames are almost hypnotic, wavering in a wind that couldn’t possibly blow down here. A wandering breeze from the surface? Or a larger creature down below?

The lizardman is pretending to be dead, and attacks any adventurers foolhardy enough to pry an eye from the idol.

Rewrite this text into something that’s more legible and appropriate for use as a room description.

There’s no right or wrong answer. This is a chance to think through decluttering convoluted text.

Reread what you wrote. How do you feel about it? Would you like using it as you run your game?

Again, there’s no right or wrong answer, but here’s what I came up with:

I want to reinforce again that you should not be writing for publication, but instead for personal completion in order to run ASAP. Getting too caught up in the formatting for each key has exhausted me in many projects that sit at 80% completion: “Good enough for the home game!” is better than “Perfect for publication.” Having a fully keyed 30+ room dungeon ready to play is a great feeling and one you’re on your way to having.

Wrapping up

In the next chapter, we’ll put the axioms we discussed to work as we begin building out the rooms of your dungeon.

Further reading

This Gus L. character is interesting to me and I would like to subscribe to his newsletter

Gus L. is prolific in the OSR scene, and has over his long career offered his opinion about most salient subjects.

- You can find his (award winning, best selling) adventures here.

- You can read his first blog here.

- You can read his currently-updating blog here.

How can I write even shorter, punchier room descriptions?

The key things here are speed, flexibility, and creativity. I do it this way, because I am in constant engagement with the players.

I look down at the tick room, and I see enough information to tell me everything I need to run the encounter successfully in seven words. The next time I will have to disengage from the players is to read the Ticks stats!

On Set Design by Courtney Campbell lays out an alternate pattern for keying rooms that is very terse. If you are better at remembering your intentions better than I am, perhaps this alternate method would work for you!

In contrast, Miranda at In Places Deep offers a middle ground in her post How Many Notes Do you Need?.

What’s a historical perspective on how room keys have been used in the hobby?

The most common style in published modules (and also probably the oldest, as you can see it in some of the earlier modules, such as B2) is the dreaded wall of text. Areas are described in lengthy, proper English prose. … Another older approach is the minimal key, exemplified by the few extant photos of Gygax’s Castle Greyhawk key. This is easy to use, but suffers in terms of being able to encode any kind of complexity.

In Improved Area Keys, Brendan at Necropraxis provides a little historical context on how room descriptions have been used in historic D&D modules and offers some opportunities for improvement.

All spot art in this chapter (and this course!) by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

This name is meaningless. Room names are not dramatic chapter titles, but tools to help the referee keep the dungeon organized. A meaningful name that describes the room contents, something like “Melted Shrine” or “Sludgemen Processional”, would both be better for this room. Worse, there’s no number to indicate what room this is on the map! ↩

No it doesn’t! The designer doesn’t tell the party how to feel, and this description doesn’t add anything to the room while wasting the valuable first impression of the room! As a designer, if you want a room to be depressing, you’ll need to write a depressing room with evocative details that capture the mood. ↩

Who? What? How does anyone know this? Such references are acceptable if the “Sludge King” or similar past room resident is an active part of the adventure, but in general one wants to leave them out. Then we have the name. As fantasy names go Blotomax isn’t the worst, but it’s neither memorable or especially useful. Stick to descriptions in the key and don’t fill the space with irrelevant information that is either inaccessible to the PCs or unrelated to the dungeon. ↩

How do they know about the golden treasure here? Can they see it? This sort of narrative aside is much like putting emotions in the character’s heads: it’s confusing, wasteful and inappropriate to the playstyle of dungeon exploration. The players control what their characters do, and they get to decide how alluring golden treasures are—when they can see them. ↩

If something is called dangerous it needs to be dangerous to the party: give the how, why, and mechanical effect of that danger. ↩

Don’t write about the room’s past if you can help it. The party usually doesn’t care or need to care and it doesn’t help the referee trying to make sense of things. If you want to design a dungeon with a history, this history has to be accessible to the players through descriptive clues, not flat statements about the past. ↩

Who? Lore is fine, but stick to what the party can actually uncover with investigation—-faceless, melted statues aren’t likely to be identifiable, and certainly the players are far more likely to want to know if a piece of dungeon dressing is dangerous or valuable before they begin to care about its former meaning. Material and color are both more useful here than the name of some saint. ↩

Keep your poetic phrases and such short and don’t overuse them. A multi-step metaphor (melted candles at a feast) requires the reader to visualize a second scene while trying to imagine the one you have keyed. Don’t do that, visualizing one imaginary space is enough. “Melted candles” would be good enough here. ↩

Why would they cross it? Why is it dangerous? These are the obvious failures here, and have been mentioned above, but the other problem here is that it seems to assume the party is entering from a specific direction. Avoid this. ↩

First, the party should be able to see this from the door 5’ - 10’ away. Second, the map should show this. The only exception is for secret doors, or other special entrances and exits, but they should be dealt with individually as a room item, rather than as part of a catalogue of ways in and out of the location. Lastly, this space seems small for what’s in it. While room dimensions aren’t especially important, some amount of attention needs to be paid to them to avoid absurdities, like 12 sludgemen marching through a 5’ corridor next to a series of doors the party may emerge from. ↩

What central chamber? Above a 10’ square building was mentioned, but not a central chamber. When you name room features try to use the same terms for them so a reader moving quickly isn’t confused. This entire space could be, and should be a separate room (or maybe a sub room. Also there’s no need to describe the room’s past. ↩

That’s interesting, but how does this work, where is this thing in the room? When you have a complex space or artifact, take care to explain how exactly it looks, especially if it’s something the players will want to interact with or which looks ominous (like a gold orb balanced on a skull). For example, “At the center of the rotted marbled pavilion is a plinth that bears a yellowed skull with a fist sized golden orb resting in the dished cranium.” ↩

This treasure description not only lacks a meaningful physical description of the treasure, but also fails to explain exactly how much it’s worth, how big and heavy it is, and if the party can do anything with it. It also includes several of the previously described errors; see if you can spot them all. ↩

It’s great to give monster action information, both the idea that the sludgemen are walking in a procession around the old shrine and that they don’t want to be interrupted. However, their goals and actions should be described clearly. ↩

Are these worth anything? Silver candlestick holders big enough to use as a club sound valuable. Generally, if something is described in a way that sounds like it contains valuable materials or is a work of art, the referee should assign a value and weight to it or note that it’s worthless—-“battered and peeling silver gilt candlesticks”, for example. Alternatively you can give them a value and weight that makes them not worth taking. ↩

The placement of this information in the key might not be incredibly bad, though it would be better to include it with information on the statues and outer part of the chamber. What’s missing here is any meaningful description of the secret trapdoor or how to find it. Does one have to open a hidden panel in a statue? Shift one on its base? If the statues are tapped with a pole will one sound hollow? This sort of thing makes for interesting play and the designer should include it not leave it for the referee to sort out at the last minute. ↩