Chapter 2: Brainstorming

In this chapter, you’ll go through the ideation required to create a dungeon. Brainstorming is an important step needed to turn a blank page into a page filled with ideas that you can actually work with. We’ll discuss how to “right size” a dungeon and think about the goals of your project. At the end of this chapter, you’ll have a set of notes in your workbook about the history and theme of your dungeon that you’ll use in later steps.

Table of contents

- Defining scope

- What system?

- No story! No story? No, story.

- Theme and background

- Unblocking creativity

- Activity: Create a theme and background Activity

- Alternative Activity: Back to BasicsAlternate Activity

- Further reading

Defining scope

The first part of a journey is deciding where you want to go. Defining your scope will help you create an achievable goal and then follow through.

As we discussed in chapter 1, a dungeon is a great location for RPG adventures because it bounds the scope of the players’ choices in a satisfying way. The players can attempt anything that would be reasonable, and it’s not hard for the average person to imagine the sort of things that “reasonable” means in a space of this size. Similarly, the dungeon’s bounded space allows the GM to hold most of it in their head at the same time.1

As we discussed in chapter 1, a dungeon is a great location for RPG adventures because it bounds the scope of the players’ choices in a satisfying way. The players can attempt anything that would be reasonable, and it’s not hard for the average person to imagine the sort of things that “reasonable” means in a space of this size. Similarly, the dungeon’s bounded space allows the GM to hold most of it in their head at the same time.1

However, a dungeon still needs to be large enough to be interesting. Too few rooms and the encounters feel predictable or inevitable: no choices! The procedures a game uses to track time won’t have spun up in a dungeon of 5-10 rooms: torches are meant to gutter and go out, but won’t even start to sputter in a dungeon of that size! A game focused on dungeon crawling should have dungeons that are large enough to have meaningful choices when it comes to exploration, direction, and strategy.

These are also problems of real world space and time. Many folks play games for two or three hours once a week. An average group will explore ~3 rooms per hour of play, depending on the complexity of the puzzles, how many fights there are, the preferences of your gaming group, etc. So part of our calculus is to decide how long we anticipate your group to spend in a single dungeon.

“So You Want to Build a Dungeon,” Gus. L

“This basic scope is important because it gives the designer expectations and guidelines for size and complexity. Too much complexity or too many rooms and the players will never be able to make meaningful progress in the adventure or understand the layout. Too few rooms and too little complexity and the adventure risks not offering many choices, reducing play to a predictable set of scenes and encounters.” 2

For this course, we’re making a 30-room dungeon. Although there should never be an expectation that players need to thoroughly clear every room, finding each treasure and vanquishing every monster, we can estimate this will take about ~10 hours to explore. That’s plenty of content for four or five sessions for the average group. This is a large enough space to feel that players can take different routes, backtrack back to puzzles they encountered but hadn’t solved, and negotiate in various ways with the various denizens of the dungeon. It’s also an achievable number of rooms to write: enough to be a stretch of your creative muscles, but not feel overwhelming.

Personal or public?

The purpose of this course isn’t to make something you intend to publish; formatting for publication requires some additional considerations that ultimately can slow down the creative process, sap energy, and risk leaving the project half-formed out of project fatigue. The goal of this course is to create something you can play with your friends on a Friday night. This is a much more achievable goal!

If you’re running your own game, you can do a lot with just a few sheets of paper: one sheet for the map, a couple of sheets for the key, and your familiarity with your own content is all you need. This helps you actually get your dungeon to the table with your friends.

“Mastering the Megadungeon,” Miranda Elkins

“All D&D is hackwork and any half-assed idea that gets your game to the table is better than a perfect one that takes months.”3

Truth. Let’s get those ideas to the table.

What system?

One of the most obvious considerations is one of the most important: what game are you prepping this dungeon for?

As you write your dungeon, you’ll want to do things like list monster stat blocks for your reference during play. You’ll write these down in your selected ruleset. OSR games tend to use similar rulesets (different iterations of the original D&D rules), so would have largely interchangeable monster stats. Pathfinder would use different stat blocks.

This probably seems like a no brainer, but stay with me.

Beyond this, a game like Pathfinder or D&D 5E has expectations about how challenging a dungeon should be for characters of a certain level. The 5E Dungeon Master’s Guide provides guidance on what sort of monsters would be a challenging-but-not-overwhelming fight for a party of five players of 5th level. It has rules on how many fights that group should go through before they have a long rest. So if you’re writing your dungeon for a game with this sort of structure, it would inform your choices during the design process.

And beyond this: challenges will be shaped by the expectations of the rule system. If players have abilities like Pick Locks 45%, your dungeon might have locked doors. If players have spells like Fly, you might put in a chasm for them to fly over or a door on the ceiling 50’ in the air. Contrastingly, if the players don’t have access to the ability to fly, a door on the ceiling 50’ in the air is a problem solving challenge. What abilities the players do/don’t have access to will inform how you make choices about the content of your dungeon.

But don’t get tangled in the “maths”: At this stage in dungeon creation the idea of a monster, trap, or treasure is more important than the specific numbers needed to represent it in the game. Just write the idea down and keep moving. Everything can be adjusted later.

During this course, I’ll be frequently referring to His Majesty the Worm as my primary ruleset. The expectations of this ruleset are shared with most OSR games. If you are using a ruleset for an OSR-style game, you can follow along with your own design process very closely. If you are using a different ruleset (like D&D 5E), you will have to bring in the expectations of that system independently.

No story! No story? No, story.

RPGs are a unique type of activity. As we discussed in chapter 1, players are provided with tactical infinity—the ability to try anything in the game world and have the attempt be judged by a GM acting as a referee of the world. Because of this feature, RPGs aren’t exactly the same thing as “telling a story.”

If you want to write a dungeon, it’s possible that you have an idea in your head of how the story of the adventure might go: 1. There’s a dragon living in an ancient dwarven city. 2. The players first will solve the riddle of the hidden door. 3. Then the players will fight and kill the dragon. 4. Then, as they exit the dungeon with the treasure, they’ll be challenged by the elves who claim the treasure as their own. 5. Then, they’ll make peace with the elves through diplomacy.

You can imagine a story being told that way. But what if that’s not what players choose to do in your game? What if they can’t solve the riddle of the hidden door (they’ll never even see your dungeon!). What if the players want to use diplomacy with the dragon but fight the elves to death? Because RPGs are all about player choices, saying “No, you have to follow the plot I wrote” isn’t fun for anyone.

When designing a dungeon, you’re designing a space charged with potential energy. You’re not designing a linear story to be solved in a certain way. Instead, prep situations that are interesting. Provide puzzles that have no one obvious solution, but many possible non-obvious solutions. Create open-ended challenges that engage your players’ creativity, and see what happens as they explore the space in a realistic way.

Don’t imagine a prescribed adventure—it’s not a sequence of scenes. Define a space, a situation, and a cast of characters. Then, after the game, the story of what happened becomes the story of the dungeon.

What you will also find, reader, is how much less work a dungeon takes to maintain and run because it’s loaded with potential energy—like an RPG battery. Your initial couple of working sessions of creativity fuels several sessions of play. And because you’re not trying to maintain the careful balancing act of a story and or fighting your players’ decisions, this makes running a game less burdensome, freeing more energy for the act of running a game.

Dungeons create an elastic game atmosphere that alleviates many of the issues that stymie modern groups: absent players, players forgetting details, players not following the exact anticipated order of events, etc.. Dungeons tolerate distraction and interruption. And playing in a dungeon can occupy both an eight-hour weekend session and a one-hour lunch time session; its old format that survives the brackish waters of players’ modern time constraints—a true bull shark!

Theme and background

This is not to say that your game world doesn’t have stories in it! A dungeon that’s just a random cave with various monsters waiting to fight to the death in every room is boring. A dungeon that is a cave carved by the tunneling of a long-dead lava worm, now inhabited by morlocks who believe themselves to be the true heirs of the local kingdom who were unjustly driven underground is much more interesting. Define your dungeon with both a theme and a background.

A theme is just the basic idea of the dungeon: an ice dungeon, a fire dungeon, a tooth fairy dungeon, etc. You know, like Mario levels. The theme allows you to riff and come up with interesting ideas for your players.

A background provides the historical details and lore for the dungeon. In broad strokes, decide:

- Who built the dungeon?

- Who lives there now?

The tension between the original purpose of the dungeon and the current inhabitants will create an interesting setting for adventure. Furthermore, the background will ground the work in the fantastic fiction, allowing you to flesh out sections of your dungeon based on the logical conclusions of the historical details.

A couple examples

Theme: Glacier dungeon

Background: Home to the Winter Queen, a fairy (daemon) of ice. Basically Jadis from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Shipwreck of a famous ship embedded in it, human treasures still to be found within the wreckage.

Theme: Mushroom swamp

Background: Once a beautiful mushroom forest growing out of the body of the mushroom god. Now, the mushroom god has a piece of a giant’s spear lodged in its brain. While the god lies dying, the swamp is poisonous. The mushroom men that live there have been driven insane.

Theme: Giant’s castle

Background: Giants once ruled mankind. This castle is a testament to their faded glory; every step is a boulder to climb, every table a mountain. The true titans are now all dead. Only the degenerate ogre sons live here now, craving the human flesh they once ate.4

Unblocking creativity

There is no tyrant as cruel as the blank page.

For many people (especially me), being told “Write a story! It can be about anything!” is neither a compelling or welcoming prompt. Its open-ended nature does not fill me with the wonder of possibility. “Write a story about your summer vacation” is a much easier prompt because it’s more specific. This is an example of how restrictions actually foster creativity!

If you are ever having trouble creating ideas in this course, choose a prompt as the starting point for whatever work you’re doing. The prompt can be anything you want: an image, a tarot card, an illustration, an I-Ching hexagram, two combined results from random tables, etc. There’s a special type of creativity that unlocks when you force yourself to write about one specific thing.

To the goal of defeating the blank page, I put together twenty-one “dungeon seeds” in His Majesty the Worm to serve as inspirational prompts for your dungeons. This chapter of the book is released as a free supplement. Use them as a starting point if you’re ever stuck during your design process.

Activity: Create a theme and background Activity

In this activity, you brainstorm some ideas and decide on a theme and background for your dungeon.

Here is a Google Doc to use as you follow along with this course.5

Tool

Alternate Workbook: Here is alternate workbook made using Google Sheets. The Google Doc workbook makes frequent use of tables to organize information. Sometimes, this can create pagination issues when there’s a lot of text in a single table. The alternate workbook avoids this issue. If you use the alternate workbook, just remember that things like page number references will be different!6

Tool

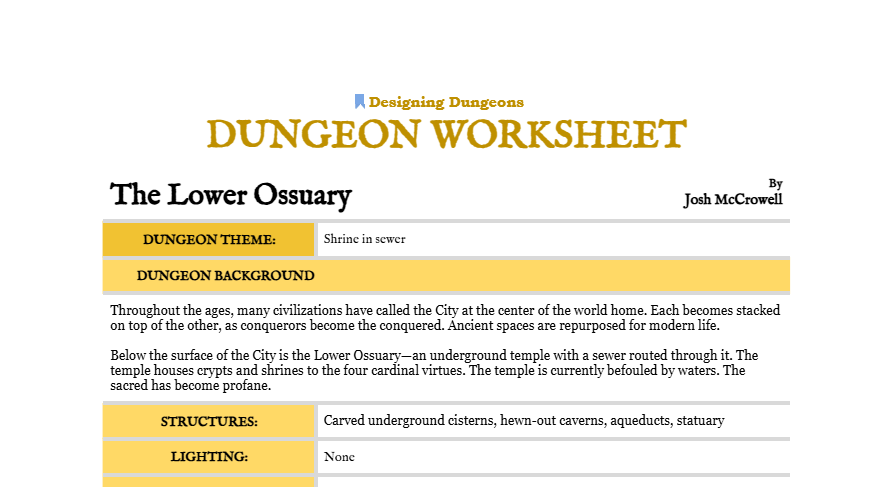

If you want to see my version of the workbook with this activity complete, check it out here.

Step 1. Create a copy of the Designing Dungeon Workbook

First, create a copy of the workbook for yourself.

- Select File

- Select Make a copy

- If you want, personalize your copy of the workbook’s name

- Optionally, delete the instructions on page 1 now that you’ve made your copy

Step 2. Define your theme

Go to page 3: Dungeon Worksheet.

Write down your dungeon theme. Make this short and punchy, easily gettable: one or two words is fine. It shouldn’t be longer than a sentence.

Step 3. Free writing exercise

Next, go to page 2: Free writing exercise. On this page, write down as many ideas about your theme as you can. Write lists of things you think are cool (laser eyes! fire breath! bats with human faces!). Write down simple puzzle set ups. Write potential rooms that you might want to include. Write types of treasure you might want to include. Just freely associate simple ideas. You will build them out later.

Spend at least ten minutes on this; set a timer.

During this time, guard yourself against distractions—don’t look at your phone, don’t check your email, don’t scroll on your favorite website. It’s just you versus the blank page.

Don’t delete or rewrite. Just put your ideas as you have them.

Write until the timer goes off.

Step 4. Define your dungeon’s background

Now that you have spent ten minutes thinking about your dungeon’s theme, you should have a clearer picture of what that dungeon is about.

At the top of the Dungeon Worksheet, write your dungeon’s background. Write one or two sentences for each of the following:

- Who built the dungeon?

- What was the dungeon’s original purpose?

- Who is the primary power that resides in the dungeon currently?

And that’s it! In future chapters, you will build these ideas out using concrete details.

Remember

If you don’t like anything you wrote today, you don’t have to keep it. You can change it during future steps.

If you haven’t already, look at my completed Dungeon Worksheet. I’ll be working more on this project throughout this series.

Alternative Activity: Back to BasicsAlternate Activity

If you’re making a dungeon using B/X procedures, consider this alternate activity instead.

In the 1981 Basic D&D by Tom Moldvay, a brief prescription is given for writing a dungeon. First is to place important magic items, treasure, and monsters.

Then, randomly stock the rest of the rooms with a simple d6 roll:

- 1-2: Monster (50% chance of guarded treasure)

- 3: Trap (~30% chance of trapped treasure)

- 4-5: Empty Room (~15% chance of hidden treasure)

- 6: Special (which are unique rooms)

So it might be helpful to simply start listing six monsters, traps, special rooms, and treasures that are thematic to your desired dungeon. Don’t worry about how exact or correct they are, as outlined above we are simply trying to flesh out the flashes of creativity that often inspire us to pursue dungeon building in the first place. You can certainly add more than six but it adds a nice symmetry with the original stocking table and six is a pretty non-intimidating number.

You can see my copy of the completed Dungeon Worksheet here!

Further reading

How do game designers go about prepping their dungeons?

Here are four great articles from award-winning designers about how they go about this process:

- My Process by Ben L. of Mazirian’s Garden

- So You Want to Build a Dungeon by Gus L. of All Dead Generations

- How I Write Adventures by Arnold K. of Goblinpunch

- Cairn 2E Dungeon Procedures by Yochai Gal of Cairn

Going for a more old-school approach (aka doing the alternate activity)?

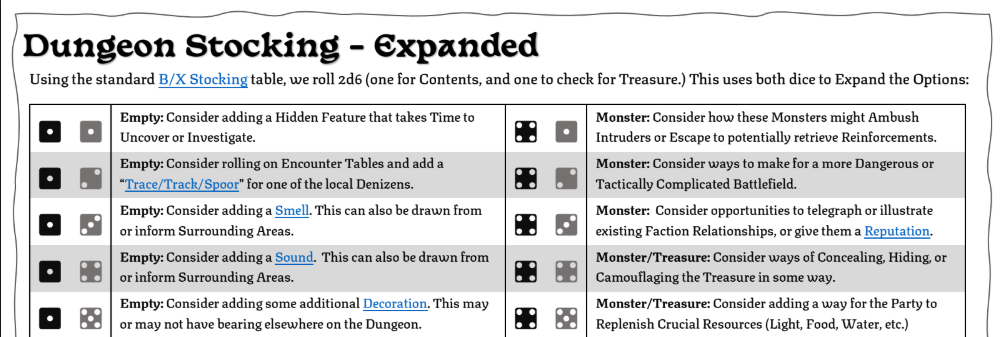

These random stocking procedures are a great starting point to write towards prompts: Dungeon Stocking Expanded

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

This workbook was adapted from the Dungeon23 Worksheet by Gus L., which was released under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial license. ↩

Special thanks to Juli from Discord for putting together the alternate workbook! ↩