Chapter 1: Course Overview

This chapter provides a high-level overview for the course Designing Dungeons: Or How To Kill A Party In 30 Rooms or Less. I’ll introduce the goals of the series, discuss my theoretical approach to design, talk a bit about myself, and provide the tools used in this course.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Who are the authors?

- An old-school approach

- Why dungeons for our dragons?Theory

- Further reading

Introduction

Role-playing games have been around for fifty years, ever since Dave Arneson had a brain hemorrhage that was lovingly cared for by the world’s worst shoe cobbler, Gary Gygax. Over these five decades, humans have said “I go into the dungeon” and then “You’re dead” over and over and over.

As a GM, creating a dungeon can seem daunting, but it’s really just a series of small, discrete tasks. The creation process is fun for the GM and the discovery process is fun for the players.

In this series, I provide practical, step-by-step instructions on how to make a 30-room dungeon that is fun to play. You’ll learn the nitty gritty of writing a dungeon from inception to completion: drawing the map, numbering the rooms, populating them with monsters, hiding treasure, and putting together notes that you can use at the table.

Together, we’ll create a dungeon. Like Bob Ross, you can follow along at home using the provided workbook. At each step, I’ll talk through the design choices and philosophy of why I do things a certain way. And, like Bob Ross says, there’s no wrong way to do things—you can make different choices as you follow along. At the end, we’ll have a working dungeon you can actually run at the table.1

You do not need a course to run dungeons

Something I have noticed is a trend of newer players shying away from running games or creating their own content because they don’t think they’re “good enough.” This sentiment feels especially prevalent after D&D’s upswing in popularity during the covid pandemic, with the rise of highly-manufactured reality TV actual plays and professional GMs. It breaks my heart because, of all art forms, RPGs are the one of the most generally accessible. You do not need a course to GM or to create your own content.

With good gaming groups, games are fun. You’re rolling dice, drinking beer, and smearing Cheetos stains on your character sheet with greasy fingers. Your friends are funny. As you role-play together, you’ll gloss over bad experiences. Good players will be charitable about the missteps of a good GM (and vice versa).

Even sorta bad dungeons can be fun at the table.

So no matter what you do, you’re going to have fun role-playing. This stuff is not super important.

That said, after playing for a long time, I know I have more fun when I approach games in a certain way. I enjoy the craft itself. That’s why I’m writing this.

GMing is something everyone can do, and do well, right from the start. There’s no DMV to go to to get your GM license. But GMing is also something you can get better at. I have been playing for many years, and every year I feel like I’m learning more about it. So if you’re interested in improving your skills, you will get hands-on experience by going through this series.

Who are the authors?

Josh McCrowell

My name is Josh. At my day job, I’m a technical writer. In the evenings, I blog about RPG stuff. I wrote a game called His Majesty the Worm. I am combining these three professional interests into this series: I am using my career of instructional design to tell you how I play games. This makes me the most boring person alive.

My game His Majesty the Worm is very focused on dungeon crawling. It’s intended to support megadungeon campaigns. To this end, I dedicated an entire chapter on the subject of writing dungeons, which culminated in a tutorial dungeon level with commentary. You can check out this chapter for free, here. This course is going to repeat some of this content, but it’s also going to expand it with practical examples.

When you see a green callout like this, this is Josh talking about his approach to dungeon design using His Majesty the Worm. This advice is a little more specific and less “general old-school.”

Warren D.

My name is Warren. I, too, blog about RPG stuff at the ICastLight! blog—mainly the OSE/BX games I run and play in on a weekly basis. I started my RPG journey with TMNT and Other Strangeness and AD&D 2e (plus Planscape & Ravenloft) along with a healthy smattering of Shadowrun and Battletech. After a long stint in boardgames, I returned to D&D via 5e, but shifted into the old-school scene after finding its DIY-attitude, creativity, mythic underworld-focus and play-centered approach energizing. The scene’s collective wisdom really reduces a burden on GMs allowing more games to hit the table. And this energy, excitement, and collected wisdom about dungeon design is what I hope gets imparted here!

When you see a blue callout like this, this is Warren is talking to you directly. He often talks more specifically about B/X D&D.

An old-school approach

Alright, time to use some acronyms and jargon. This is just to set expectations.

In the aughts, there was a movement in RPG design called the Old-School Renaissance/Revival (OSR). It reexamined and reimagined the earliest editions of RPGs, extracting lessons for modern design. It emphasized problem solving, player choice, and simple, open-ended rulesets.2 It had settings that were at once realistic and down to earth and completely off the wall and swarming with magic robots.

Dungeons are central to play in “old-school” D&D. As such, the OSR thought a lot about what makes dungeons actually fun in practice. The OSR thinks about dungeons in a different way than, say, a Dungeon World module or a Pathfinder adventure path. Its best practices and principles are exemplified here.

New to the old school?

See “Further reading” for links to more information.

Why dungeons for our dragons?Theory

While there are lots of ways to approach RPGs, one of the unique things about this style of game is that players have “tactical infinity.” That is to say, because the players’ actions are adjudicated by a game master (GM, also called a “referee” in old-school games), a player can potentially have their character do anything. In a video game or a board game, your character can only do those things the game designers have anticipated you doing. Is there a low stone wall in a video game? Well, that blocks your character. In an RPG, you can do anything that is realistic in the world of the game.  You might climb the wall, hire a team of workers to tear it down, or train a dire mole to tunnel under it. You can try to do anything, because a real human is on the other side of the table telling a story about what actually happens based on your input.3

You might climb the wall, hire a team of workers to tear it down, or train a dire mole to tunnel under it. You can try to do anything, because a real human is on the other side of the table telling a story about what actually happens based on your input.3

OSR games really value this kind of free input. One of the values of OSR games is that players should always have the ability to make informed, meaningful choices. Being able to make impactful choices elevates what makes RPGs special as a medium.

Thus, dungeons

Dungeons are an important element of fantasy adventure play because good dungeons are full of meaningful choices to be made. How do you get across the spiked pit? Do you accept the chained ogre’s offer to set him free in exchange for a key to the treasure room? What do you do when you see a pile of gold sitting “undefended” in the middle of a room?

In a small, self-contained space, the players’ choices in a dungeon build on themselves in a satisfying way. The players really feel that their choices matter when they fall to their death, get filthy lucre in exchange for the safety of the peasants of the nearby village, and cleverly avoid a hidden trap guarding the treasure.

A dungeon offers something to both new gamers and veterans. A dungeon is a contained environment to practice the call-and-response form of play of RPGs. It’s a discrete space that allows players to try anything, but limits logical choices. There are pits, but the player can’t just borrow a pit-crossing ladder from their neighbor Bobert. (This kind of gameplay has more twists and turns both in wilderness hex crawling and urban, city-based games.)

Finally, the almost universal idea of the “underworld” as an environment closer to dream, death, and divinity makes the space a universally understood and highly miscible setting for as many themes a creator might want to apply.

Jaquaysing the process

Creating a dungeon is mostly a non-linear process. This course is ordered in a series of discrete steps to help us make sense of what is, in practice, unsequenced work. As you take the lessons you learn here, don’t imagine you have to adhere to the rigidity of pedagogy. Jump around from section to section as you’re inspired, jot notes down on monsters while making your map, and so on.

Further reading

Each chapter includes a “Further reading” section. These are links to texts that explain core concepts of RPGs, the OSR design movement, the history of gaming, and other relevant topics. If you’re interested in following the rabbit hole on any particular subject, use these links to supplement your understanding of the dungeon design space.

New to this role-playing thing in general?

“D&D is like television. This episode might be great. Don’t you want to know what happens next episode?”

Here is a video by Matt Colville called “Welcome to Dungeons and Dragons.” In it, he talks through the basic expectations of the game: how often people play, what you do during play, etc. Great top level summary!

New to the OSR?

“Don’t prepare a plot for the players to follow. During the game, observe how players deal with a situation, and extrapolate the effects of their actions based on what you know. Don’t plan the results too far ahead of time; players rarely do what you expect them to.”

The Principia Apocrypha is an introduction to the principles and playstyle of old-school gaming. It is a more serious expansion of the brief introduction to the term “OSR” in this chapter.

Basic OSR principles for 5E players

“Reward creative thinking and problem solving. If a player makes a good enough argument, they shouldn’t need to roll any dice; they just succeed.”

Yochai Gal, creator of the game Cairn, also explains the framing of old-school play in his post “Basic OSR Principles.” While covering the same ground as the Principia Apocrypha, it approaches the principles for readers who are most familiar with D&D 5E, so his post is a helpful alternative framing for this audience.

Do you want to learn even more about OSR gaming?

Knock! is a series of zines that aggregate the collective wisdom and weirdness of the OSR scene. Between its covers, you can find some of the most well-known OSR essays, strange bits of apocrypha, gameable tables, funky art, new classes, and ready-to-run dungeons. It’s exquisitely produced. Some of the issues are even edited by yours truly.

Do you want to learn how to referee OSR-style games?

Arnold of Goblinpunch has released a teaching dungeon with commentary called The Mouth of Mormo. Check out the jumbo version to see his explanations of why the dungeon is structured the way it is, and how he recommends approaching rulings, combat, when to call for initiative, handling secrets, and more. Invaluable resource.

Why are dungeons the “right size”?

“The core activity of roleplaying games is making decisions. Every other activity feeds back into this core in one way or another.”

The Basis of the Game are Interesting Decisions by Retired Adventurer is an essay that discusses a simple fact about games of all sorts: making decisions is the fun part.

What are megadungeons and the mythic underworld?

Philotomy’s Musings was one of the earliest series of essays about the old-school playstyle found in the original D&D texts. It defines the mythic underworld in this way:

1. It’s big, and has many levels; in fact, it may be endless

2. It follows its own ecological and physical rules

3. It is not static; the inhabitants and even the layout may grow or change over time

4. It is not linear

5. There are many ways to move up and down through the levels

6. Its purpose is mysterious or shrouded in legend

7. It’s inimical to those exploring it

8. Deeper or farther levels are more dangerous

9. It’s a (the?) central feature of the campaign

Read the rest of the essays to become more familiar with some of the other terms used in this course.

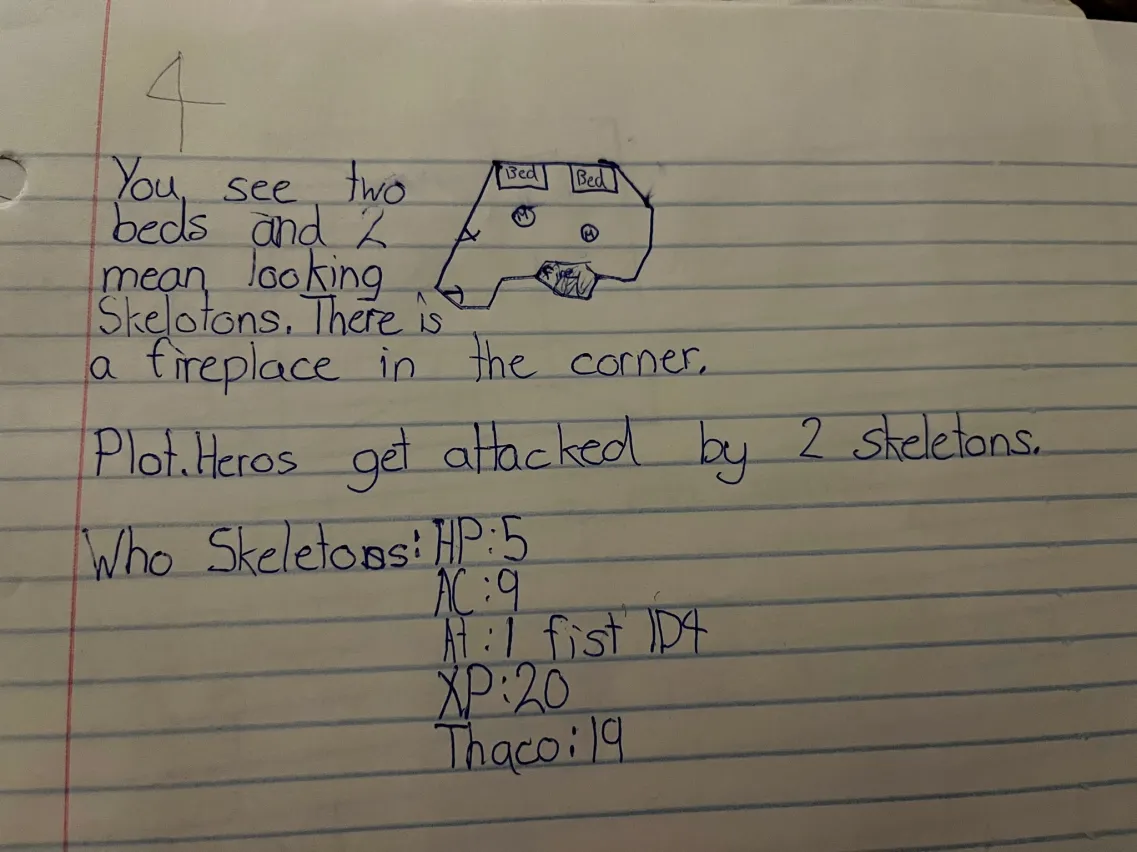

(Peak dungeon design by SavevsTotalPartyKill.)

(Peak dungeon design by SavevsTotalPartyKill.)

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩

Definition quoted from SavevsTotalPartyKill. ↩

Art by BertDrawsStuff. ↩